(Bloomberg) - With a debt ceiling deal freshly signed into law Saturday by President Joe Biden, the US Treasury is about to unleash a tsunami of new bonds to quickly refill its coffers.

This will be yet another drain on dwindling liquidity as bank deposits are raided to pay for it — and Wall Street is warning that markets aren’t ready.

The negative impact could easily dwarf the after-effects of previous standoffs over the debt limit. The Federal Reserve’s program of quantitative tightening has already eroded bank reserves, while money managers have been hoarding cash in anticipation of a recession.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategist Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou estimates a flood of Treasuries will compound the effect of QT on stocks and bonds, knocking almost 5% off their combined performance this year. Citigroup Inc. macro strategists offer a similar calculus, showing a median drop of 5.4% in the S&P 500 over two months could follow a liquidity drawdown of such magnitude, and a 37 basis-point jolt for high-yield credit spreads.

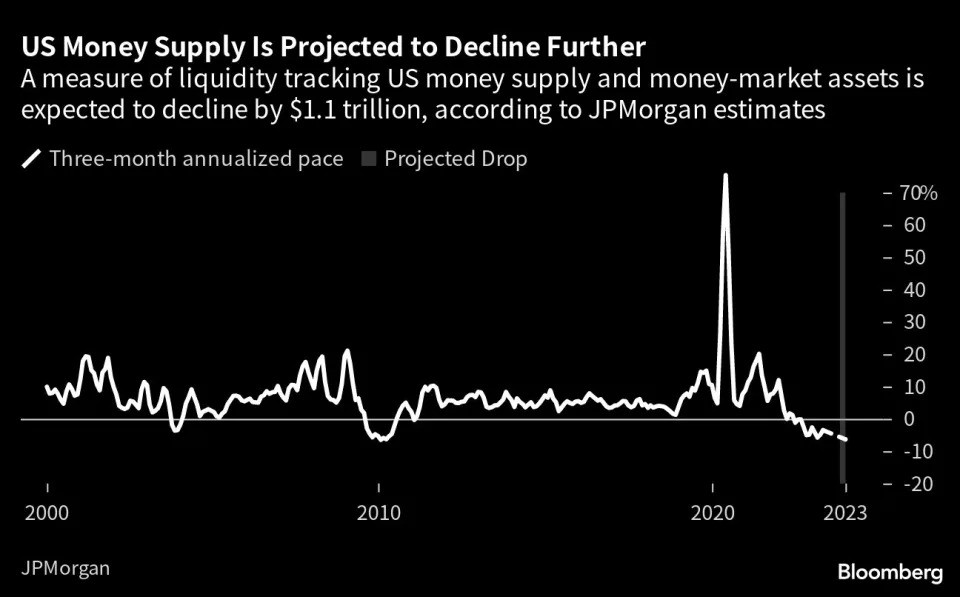

The sales, set to begin Monday, will rumble through every asset class as they claim an already shrinking supply of money: JPMorgan estimates a broad measure of liquidity will fall $1.1 trillion from about $25 trillion at the start of 2023.

“This is a very big liquidity drain,” says Panigirtzoglou. “We have rarely seen something like that. It’s only in severe crashes like the Lehman crisis where you see something like that contraction.”

It’s a trend that, together with Fed tightening, will push the measure of liquidity down at an annual rate of 6%, in contrast to annualized growth for most of the last decade, JPMorgan estimates.

The US has been relying on extraordinary measures to help fund itself in recent months as leaders bickered in Washington. The measure brokered between Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy limits federal spending for two years and suspends the debt ceiling through the 2024 election.

With default narrowly averted, the Treasury will kick off a borrowing spree that by some Wall Street estimates could top $1 trillion by the end of the third quarter, starting with several Treasury-bill auctions on Monday that total over $170 billion.

What happens as the billions wind their way through the financial system isn’t easy to predict. There are various buyers for short-term Treasury bills: banks, money-market funds and a wide swathe of buyers loosely classified as “non-banks.” These include households, pension funds and corporate treasuries.

Banks have limited appetite for Treasury bills right now; that’s because the yields on offer are unlikely to be able to compete with what they can get on their own reserves.

But even if banks sit out the Treasury auctions, a shift out of deposits and into Treasuries by their clients could wreak havoc. Citigroup modeled historical episodes where bank reserves fell by $500 billion in the span of 12 weeks to approximate what will happen over the following months.

“Any decline in bank reserves is typically a headwind,” says Dirk Willer, Citigroup Global Markets Inc.’s head of global macro strategy.

The most benign scenario is that supply is swept up by money-market mutual funds. It’s assumed their purchases, from their own cash pots, would leave bank reserves intact. Historically the most prominent buyers of Treasuries, they’ve lately stepped back in favor of better yields on offer from the Fed’s reverse repurchase agreement facility.

That leaves everyone else: the non-banks. They’ll turn up at the weekly Treasury auctions, but not without a knock-on cost to banks. These buyers are expected to free up cash for their purchases by liquidating bank deposits, exacerbating a capital flight that’s led to a cull of regional lenders and destabilized the financial system this year.

The government’s growing reliance on so-called indirect bidders has been evident for some time, according to Althea Spinozzi, a fixed-income strategist at Saxo Bank A/S. “In the past few weeks we have seen a record level of indirect bidders during US Treasury auctions,” she says. “It’s likely that they’ll absorb a big part of the upcoming issuances as well.”

For now, relief about the US avoiding default has deflected attention away from any looming liquidity aftershock. At the same time, investor excitement about the prospects for artificial intelligence has put the S&P 500 on the cusp of a bull market after three weeks of gains. Meanwhile, liquidity for individual stocks has been improving, bucking the broader trend.

But that hasn’t quelled fears about what usually happens when there’s a marked downturn in bank reserves: Stocks fall and credit spreads widen, with riskier assets carrying the brunt of losses.

“It’s not a good time to hold the S&P 500,” says Citigroup’s Willer.

Despite the AI-driven rally, positioning in equities is broadly neutral with mutual funds and retail investors staying put, according to Barclays Plc.

“We think there will be a grinding lower in stocks,” and no volatility explosion “because of the liquidity drain,” says Ulrich Urbahn, Berenberg’s head of multi-asset strategy. “We have bad market internals, negative leading indicators and a drop in liquidity, which is all not supportive for stock markets.”

(Updates with Biden’s signature in first paragraph.)

By Denitsa Tsekova and Ksenia Galouchko

With assistance from Sujata Rao, Elena Popina and Liz Capo McCormick