(Jeff Wagner, Morningstar) A quick survey of asset manager websites might leave a financial advisor wondering when and why investor behavior and related topics have become so pervasive. Some in the industry even argue that behavioral coaching is the single most impactful service an advisor can offer.

Whatever your persuasion, insights from behavioral scientists are leading to more effective ways of changing people’s behavior than mere education, which has been the prevailing approach. This paper is intended to provide financial advisors with a quick summary of how we got here, what problems behavioral scientists attempt to solve, and a tool they employ to solve them.

Research shows that behavioral guidance can have a meaningful impact on investors’ chances of reaching long-term financial goals.

A Break From Convention

For more than a century, traditional economists have assumed humans to be perfectly rational when building their economic models. This rational Economic Man makes logical, self-interested decisions that maximize expected utility in the narrow sense—that is, their choice is always the one that does them the most material good. Economic Man pursues goals by responding consistently to incentives and making appropriate trade-offs as needed. Economic Man thinks carefully about both the present and the future and anticipates the likely consequences of his actions on his material well-being.

Does Economic Man sound like anyone you know? Aside from fictional Vulcans on Star Trek, presumably not. The ideal of a perfectly rational decision-maker is useful for building economic models, but it doesn't reflect reality and can be misleading to those seeking to give useful financial guidance.

In truth, we humans are considerably less rational in our decision-making than these models presume. We have limited attention spans, finite willpower, fallible memories, and inconsistent reasoning abilities; most of us can't stick to a diet or exercise plan, for example, and we consistently show our irrationality in simple experiments by psychologists. When you consider all that goes into decision-making about your financial investments—the emotions involved, your complex personal circumstances, and the need to forecast far into the future—it’s no wonder that our real-world decisions can vary so much from those made under some ideal set of circumstances.

Importantly, the ways in which our decisions go awry are not haphazard. A new school of economists (they were influenced by cognitive psychologists) have studied human behavior and found that we tend to make irrational decisions in systematic ways. That is, we are predictably irrational, especially in particular situations.

This new school isn't about modeling human behavior but studying it in the real world. Several non-economists have won the Nobel Prize in economics, including Daniel Kahneman, whose work was popularized in the 2011 best-seller "Thinking, Fast and Slow." In it, Kahneman (based on work with his long-time collaborator Amos Tversky) lays out a catalogue of cognitive biases (more on these in the next section) as well as a notion of two general ways the brain operates—fast and slow—referenced in the book’s title. "Fast" thinking is easy, intuitive, and approximate, while "slow" thinking is effortful, deliberate, and more precise. Consider this simple math problem: A bat and ball together cost $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? Once you have your answer, check it with the reference below.

Richard Thaler, an economist, a best-selling author, and the winner of the Nobel Prize in 2017 for his work integrating psychologically realistic assumptions into economic decision-making, has applied behavioral economics to public policy and finance. In fact, much of the most influential work of behavioral economics has been in finance, and it's in the sub-field of behavioral finance that Morningstar Investment Management and our parent, Morningstar, Inc., have invested considerable resources—realizing that while we share many insights about investments, we should also provide insights about investors..

From Research to Application

The behavioral sciences have spent much of the last decades cataloging the shortcomings of people when they make decisions. This may be interesting but doesn't necessarily fix the problem. A major challenge in the coming decades will be to use these insights to help “flawed” decision-makers make better choices. This is a different approach than trying to educate people into being perfectly rational decision-makers. Rather than aim to change people (and how they think and learn), researchers find ways to change the choice environment such that an imperfect decision-maker can still make good choices.

Consider the example of enrollment in an employer-based defined contribution plan such as a 401(k) or 403(b). Traditionally, an employee had to opt in, meaning that you had to affirmatively elect to participate in the plan. As we saw with fast and slow thinking, whenever effort is involved, people are less likely to make a good decision—the easy or lazy route usually wins. And that was the case with defined contribution plans, with many people not saving anything for retirement. To help people overcome the apparent burden of enrollment, decision scientists recommended flipping the decision so that you had to opt-out of participating in the retirement plan. In one well-known study, scientists found that participation rates increased to 86% from approximately 50% just by changing the default to automatic enrollment. Similar automatic techniques have increased average saving levels in these plans.

Financial advisors have practiced client education for decades, usually in the form of informing clients on the right saving and investing behavior. While providing information is still important, research shows that education alone does not reliably change behavior. Most people know they should eat healthy food, but certainly not everyone always does. And more information (e.g., a clear ingredients list and standard nutritional information on food packaging) alone is not sufficient.

The retirement plan example above illustrates how a simple change in the way a decision is structured—something known as choice architecture—can improve decision-making and lead to better outcomes for people.

Nudging People to Better Decisions

Choice architecture is the careful design of the ways in which choices are presented with the intent of improving the outcomes and quality of decision-making. It takes the focus off self-discipline and intrinsic knowledge to facilitate decisions that are in your best interest. These are often "nudges"—to borrow a phrase from Thaler's best-selling book of the same name—or simple changes in the way information is presented that can have significant impacts on helping people overcome biases. So, instead of telling people to eat healthily, the choice architecture approach would be to put healthy foods first in the cafeteria line and in the easiest-to-reach spots. By making the best (or least bad) option the default, it is easier for people to choose the smart option quickly and with less resistance.

How can decision science help investors, and how is Morningstar Investment Management using it to help advisors? One of our core principles is putting investors first. To do so, Morningstar's Behavioral Science team thinks carefully about how investment decisions are made. In the next section, we'll highlight one process—the presentation of performance data—that can be improved by removing bias and making it easier to make good choices, all with the aim of helping advisors' clients make good financial decisions and ultimately reach their long-term financial goals.

What You Pay Attention to Matters

A major cognitive bias is recency bias, which describes the human tendency to give greater importance to the most recent event. For investors, this bias tends to emerge amid a market downturn. Even for those of us predisposed to a long-term view, our attention narrows during times of stress, convincing us that the falling market is likely to continue. And left unchecked, this bias can lead investors to make emotionally charged decisions—ones that could lead to a permanent loss of capital. Unless, that is, we can reallocate our attention to information that better serves us.

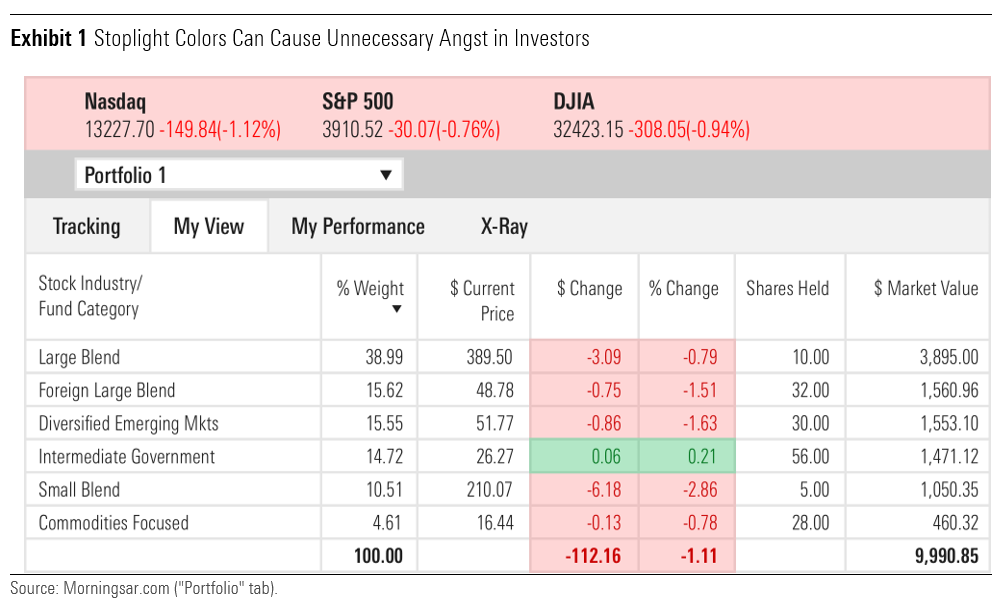

For example, market or portfolio performance is often communicated daily—if not every 15 minutes—in stoplight colors so investors can see immediately how their portfolio is doing at that moment. What’s problematic is that most people gravitate to the negative numbers, aided in no small way by the fact that they’re bright red. Markets tend to be negative frequently, even when their longer-term path is positive. When you add the effects of recency bias, seeing this negative performance frequently can make an investor think they are on the wrong path, even if they are not.

To mitigate this effect, we suggest contextualizing portfolio performance in a goals-based framework, which would likely entail displaying portfolio performance in terms of the probability of reaching an investment goal. So, instead of seeing today’s account value change in red or green, you would see your current portfolio value and its probability of reaching a predetermined savings goal over a set time horizon. Of course, you would still be able to get more investment-level detail if you want it. But by focusing investors’ attention on their long-term goals rather than today’s market environment, we might help people make better decisions and thus improve their financial wellness.

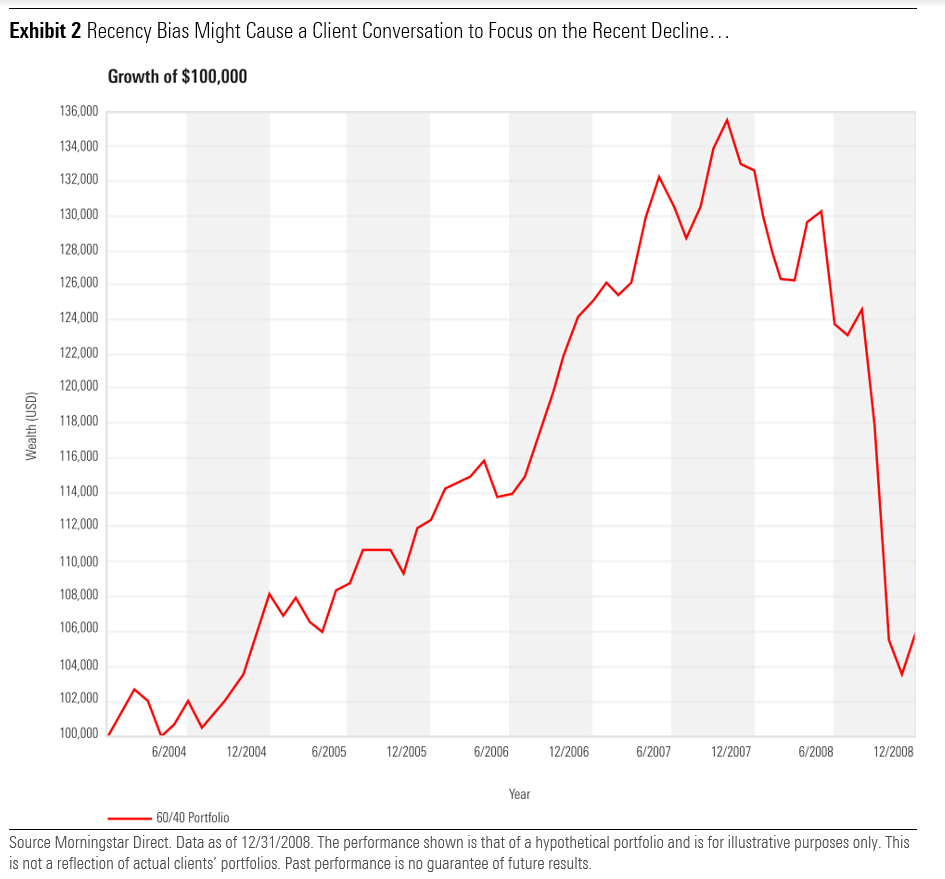

Let’s compare two charts to show the effect of performance presentation on perspective. The first chart below shows the growth of $100,000 invested in a hypothetical portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds over a five-year period through December 2008. What's important here is the shape of the return line and how an investor might interpret it in real time. At its peak near the end of 2007, the portfolio would have gained about 36% before losing most of the gains throughout the subsequent drawdown in 2008. A conversation with a client at this moment would likely center on the recent loss of account value, made worse by the high market uncertainty and the steady flow of negative reporting emanating from the financial media; essentially, a conversation primed for action, albeit the imprudent kind.

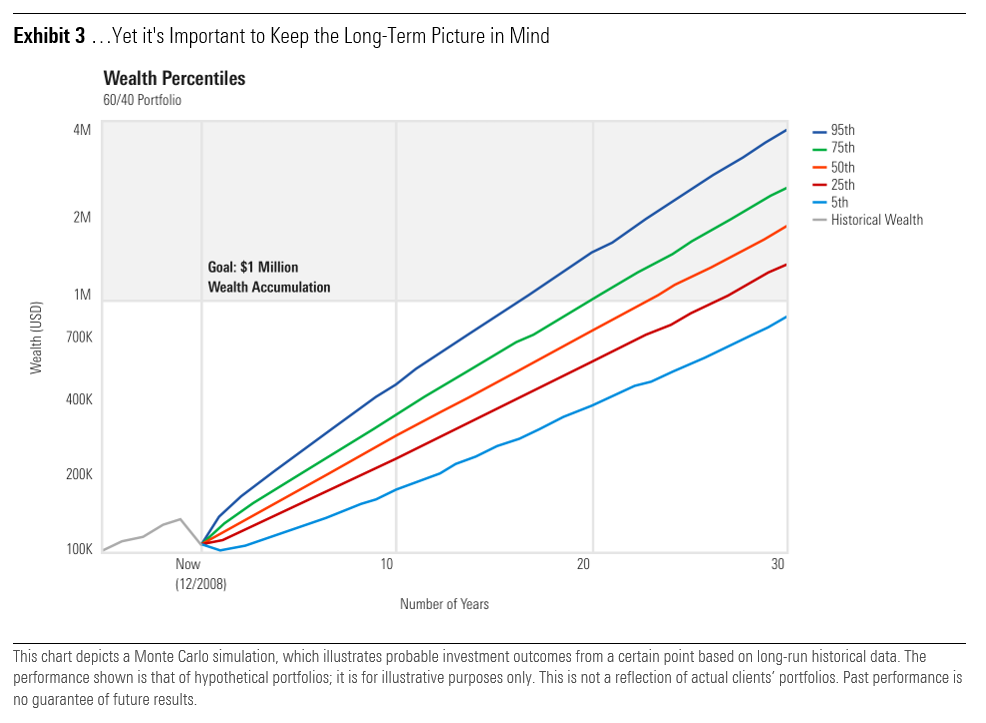

The second chart illustrates the concept of contextualizing performance using simulation software that is widely available; this is from Morningstar Direct. By entering a starting value and a few capital market assumptions, the simulation will forecast the distribution of wealth outcomes over a given time horizon. So, in this case, the starting value is the same 60/40 portfolio’s account value at the end of 2008, and the goal is $1 million in wealth in 30 years. The second chart still shows the first five years of historical investment growth as the first chart, but the focus is redirected from past performance to a future wealth outcome. Even after the large drawdown in 2008, the percentiles in this simulation show that there is still a greater than 75% chance of hitting that wealth goal (i.e., $1 million is below the 25th percentile of outcomes). Given this focus on a future state, a conversation with a client at the same moment in time should be less likely to result in an overreaction to recent poor performance, and it’s precisely the mitigation of this type of bad behavior that is in a client’s best interest.

Framing bias is the tendency to respond differently based on the context of a choice. For example, consider two scenarios. A shop levies a 3% fee on credit card purchases. Another shop offers a 3% discount for paying cash. If you would act differently in the two shops (with regards to your payment method), that illustrates framing bias.

Our proposal above is a type of reframing. Instead of focusing attention on recent short-term losses, we assess the investor's current situation in the context of their long-term goal. This removes a lot of the emotional response, and we expect it will lead to better long-term outcomes for investors.

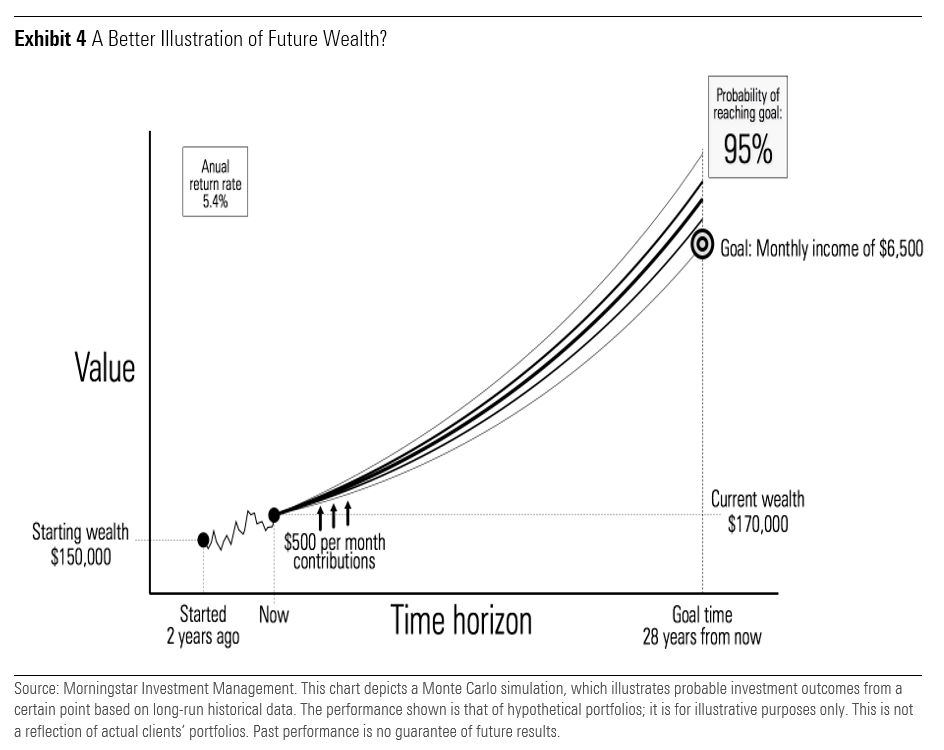

That’s a good start, but perhaps a more sophisticated representation would resonate more with investors. For example, the conceptual illustration below shows a similar scheme, but this time the goal is a monthly retirement income—presumably, what you anticipate needing to live comfortably in retirement. The underlying simulation is the same, and it would mostly entail cosmetic upgrades to produce this type of illustration.

Considering that a goal such as the ability to meet a desired standard of living in retirement may be more relatable than a wealth goal, an income goal may provide an even more convincing story to help investors stay the course during difficult times.

Adding Value With Behavioral Coaching

In recent years, behavioral science has received much attention within the advice industry and for good reason. Research from Morningstar shows that financial advice can lead to better outcomes for clients, and others such as The Vanguard Group have concluded that behavioral coaching is the greatest potential advisor value-add. Reframing performance in terms of reaching long-term goals demonstrates the powerful influence for good that behavioral science can have for investors. And we think it shows why every advisor should understand it.

Benjamin Graham said, “The investor's chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.” Advisors have long worked to prevent this. Using nudges and decision architecture can help advisors in their efforts to help clients reach their financial goals.

For more examples of how our Behavioral Science group is helping investors reach their financial goals, please visit the Investor Success Project.

Opinions expressed are as of the current date; such opinions are subject to change without notice. Morningstar Investment Management shall not be responsible for any trading decisions, damages, or other losses resulting from, or related to, the information, data, analyses or opinions or their use. This commentary is for informational purposes only. The information, data, analyses, and opinions presented herein do not constitute investment advice, are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security. Please note that references to specific securities or other investment options within this piece should not be considered an offer (as defined by the Securities and Exchange Act) to purchase or sell that specific investment. Performance data shown represents past performance. Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments involve risk, including the loss of principal. There can be no assurance that any financial strategy will be successful. Morningstar Investment Management does not guarantee that the results of their advice, recommendations or objectives of a strategy will be achieved. This commentary contains certain forward-looking statements. We use words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “believes”, “estimates”, “forecasts”, and similar expressions to identify forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results to differ materially and/or substantially from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by those projected in the forward-looking statements for any reason. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Morningstar® Managed PortfoliosSM are offered by the entities within Morningstar’s Investment Management group, which includes subsidiaries of Morningstar, Inc. that are authorized in the appropriate jurisdiction to provide consulting or advisory services in North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa. In the United States, Morningstar Managed Portfolios are offered by Morningstar Investment Services LLC or Morningstar Investment Management LLC, both registered investment advisers, as part of various advisory services offered on a discretionary or non-discretionary basis. Portfolio construction and on-going monitoring and maintenance of the portfolios within the program is provided on Morningstar Investment Services behalf by Morningstar Investment Management LLC. Morningstar Managed Portfolios offered by Morningstar Investment Services LLC or Morningstar Investment Management LLC are intended for citizens or legal residents of the United States or its territories and can only be offered by a registered investment adviser or investment adviser representative. Investing in international securities involve additional risks. These risks include, but are not limited to, currency risk, political risk, and risk associated with varying accounting standards. Investing in emerging markets may increase these risks. Emerging markets are countries with relatively young stock and bond markets. Typically, emerging-markets investments have the potential for losses and gains larger than those of developed-market investments. A debt security refers to money borrowed that must be repaid that has a fixed amount, a maturity date(s), and usually a specific rate of interest. Some debt securities are discounted in the original purchase price. Examples of debt securities are treasury bills, bonds and commercial paper. The borrower pays interest for the use of the money and pays the principal amount on a specified date. The indexes noted are unmanaged and cannot be directly invested in. Individual index performance is provided as a reference only. Since indexes and/or composition levels may change over time, actual return and risk characteristics may be higher or lower than those presented. Although index performance data is gathered from reliable sources, Morningstar Investment Management cannot guarantee its accuracy, completeness or reliability.