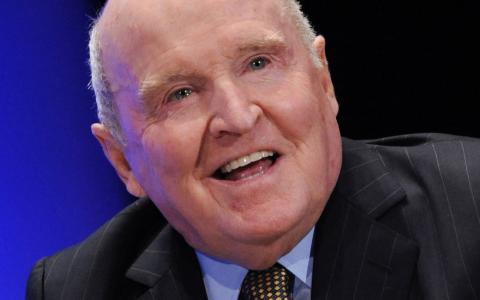

Jack Welch, the champion of corporate efficiency who built General Electric Co. into one of the world’s largest companies and influenced generations of business leaders, has died. He was 84.

His death was reported Monday by CNBC, which cited his wife, Suzy.

The former GE chairman and chief executive officer, whose blunt style and ceaseless cost cutting earned him the sobriquet “Neutron Jack,” mentored proteges who went on to run some of the world’s best-known companies. Named “Manager of the Century” by Fortune magazine in 1999, he presided over a stock surge of almost 3,000% during a two-decade tenure before his legacy was dented in retirement by GE’s bruising share plunge.

“He became the gold standard of greatness, the icon of industrial imagination,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a Yale University business professor who knew Welch since the 1980s. “His track record over those 20 years as CEO is hard to see excelled anywhere.”

Known simply as Jack to even low-level employees, Welch became the youngest CEO in GE’s history in 1981. He created a leaner company, yet one whose dependence on finance would eventually prove to be a threat. Along the way, he molded GE’s culture to reflect his demanding personality, one larger than his 5-foot-7-inch (1.7-meter) frame.

“I like challenging people. I like debate. I like all those things,” he told interviewer Charlie Rose less than two months after his 2001 retirement. “And yet I love having a drink with ’em, too.”

Second Career

Welch stepped down four days before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. He remained active for more than a decade as a consultant and media commentator.

Business leaders extolled his ability to boost profit and shareholder wealth with his restless, results-driven approach. GE became the world’s biggest company by market value at more than $500 billion in 1999.

Imitators across corporate America copied his leadership strategies, and recruiters snapped up lieutenants including W. James McNerney Jr., who later became Boeing Co.’s CEO, and Robert Nardelli, who ran Home Depot Inc. and Chrysler. Another GE executive, Jeffrey Immelt, would best them to succeed Welch.

Welch’s legacy took a blow after he retired. The shares would lag behind the pre-Sept. 11 level for virtually all of Immelt’s 16 years as CEO. GE lost more than $200 billion in market value in a two-year stretch ending Dec. 31, 2018. The company’s latest CEO, Larry Culp, has overseen a partial comeback.

Soon after Enron Corp. collapsed in late 2001, GE found itself facing accounting questions about whether Welch relied on moves such as one-time asset sales to produce consistently steady profit gains. GE Capital under Welch grew so vast that unit’s struggles in the 2008-2009 financial crisis would imperil all of GE. The company has since exited nearly all of the lending businesses.

Finance Revisited

“There’s been some revisiting of the robustness of the financial services model. GE Capital was providing cover for some other parts of the business,” Sonnenfeld said. There was a “backlash that did dog Jack Welch.”

John Francis Welch Jr. was born Nov. 19, 1935, in Peabody, Massachusetts. He was the only child of John Sr., a Boston & Maine Railroad conductor, and Grace Andrews Welch.

Growing up in Salem, Massachusetts, he was outspoken and athletic. He played golf, hockey and baseball at Salem High School, where he was voted “most talkative and noisiest” boy by classmates and wrote in the school literary magazine that he wanted to “make a million.”

Welch’s mother infused him with self-confidence and helped him overcome a boyhood stutter -- “the most influential person in my life,” he wrote in his 2001 autobiography “Jack: Straight From the Gut.”

‘You Punk!’

After a close hockey defeat as a youngster, Welch flung his stick across the ice, prompting his mother to march into the locker room, grab him by the jersey and shout: “You punk! If you don’t know how to lose, you’ll never know how to win.”

In 1957, he graduated with honors from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst with a bachelor’s degree in engineering. Three years later, he received a doctorate in chemical engineering from the University of Illinois and took a $10,500-a-year job with GE in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where the company developed new businesses in plastics.

Working his way through the ranks from vice president to vice chairman, Welch gained a reputation as a maverick, questioning whether GE was being run the right way. He saw GE’s future in plastics, medical equipment and financial services, not household appliances.

Winners, Losers

At 45, Welch succeeded Reginald Jones as chairman and CEO. While GE was profitable, Welch was concerned that it was too big to be flexible. He sorted GE’s divisions into “winners” -- those first or second in their industries -- and “losers,” mostly older units that had to improve or face disposal.

Over a five-year span in the 1980s, he sold more than 200 businesses and closed dozens of factories. Annual dismissals of the 10 percent of employees deemed the lowest performers also became standard. Welch’s moves would shrink the workforce by one-third to 239,000 people.

“A successful leader can shock an organization and lead its recovery. An unsuccessful leader will shock an organization and paralyze it,” Welch said in a 1994 Industry Week interview. “Organizations constantly need to be regenerated.”

GE under Welch spent more than $25 billion on acquisitions, and he pushed into finance as the U.S. economy shifted away from manufacturing. He looked overseas, too, boosting foreign sales by more than 50 percent.

He pioneered widely imitated training programs, including “Work-Out,” in which employees learned to accelerate decision-making with days of brainstorming. In 1995, Welch implemented the Six Sigma quality controls to improve manufacturing processes. Noting GE’s success, companies around the world would adopt a similar methodology.

‘Tremendous Passion’

Welch knew thousands of employees by name and would send handwritten notes to voice his approval or dissatisfaction.

“He had tremendous, tremendous passion for the business, but he also had tremendous passion for people,” William Conaty, whose 40-year GE career included serving as human resources chief under Welch, said in a 2014 interview. “If your wife was sick, he’d want to know how she was doing.”

Welch also worked six days a week, taking only Sunday off to golf -- he called working weekends “a blast” -- and expected similar dedication from those who wanted to get ahead.

“I never once asked anyone, ‘Is there someplace you would rather be -- or need to be -- for your family or favorite hobby or whatever?”’ he said in his 2005 book, “Winning.”

Welch delayed his mandatory age-65 retirement for almost a year for a final challenge: a $53 billion bid for Honeywell International Inc. that collapsed when he balked at European regulators’ demands for concessions.

Baseball, Golf

A lifelong Boston Red Sox fan, Welch would test executives and potential hires on their baseball knowledge. He was also a golf addict, hitting the links with Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton and executives including Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.

After leaving GE, Welch served as a part-time adviser, a partner at investment firm Clayton Dubilier & Rice and consultant to companies including JPMorgan Chase & Co. He taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s business school, opened a management institute bearing his name and stayed in the public eye with guest-host gigs on CNBC and New England Sports Network.

Welch married Carolyn Osburn in 1959, and they had four children before divorcing in 1987. He was married to corporate lawyer Jane Beasley for 13 years. They divorced in 2002 amid revelations of an affair with Harvard Business Review editor Suzy Wetlaufer that began when Wetlaufer was interviewing him for an article.

The two married in 2004 and went on to collaborate on “Winning,” but not before divorce proceedings opened a public argument over Welch’s fortune, with his second wife’s lawyers claiming his asset valuation of $456 millionwas at least $100 million too low. The case was settled in 2003.

By then, Welch’s retirement package had been shown to include his $11 million Central Park West apartment in New York City, use of a private jet, a leased Mercedes-Benz, restaurant and laundry expenses, country-club fees and sports tickets. He later opted to pay for some perks himself.

This article originally appeared on Bloomberg.