Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell on Tuesday reaffirmed the U.S. central bank's intent to encourage a "broad and inclusive" recovery of the job market, and not to raise interest rates too quickly based only on the fear of coming inflation.

"We will not raise interest rates pre-emptively because we fear the possible onset of inflation. We will wait for evidence of actual inflation or other imbalances," Powell said in a hearing before a U.S. House of Representatives panel.

Recent price increases have pushed the consumer price index to a 13-year high, prompting Republicans on the committee to offer charts detailing spikes in consumer items like bacon and used cars to suggest price increases are getting out of hand.

"We have unstable employment and higher inflation," said Representative Jim Jordan, an Ohio Republican, referring to the Fed's congressionally mandated goals of ensuring maximum employment and stable prices. "Something has to give."

The recent high inflation readings, however, "don't speak to a broadly tight economy" that would require higher interest rates, Powell said, referring to a "perfect storm" of rising demand for goods and services and bottlenecks in supplying them as the economy reopens from the pandemic.

Those price pressures should ease on their own, Powell said.

In setting upcoming monetary policy, the Fed chief pledged that the central bank would keep its eyes focused on a broad set of labor market statistics, including how different racial and other groups are faring.

"We will not just look at the headline numbers for unemployment," Powell told the members of the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis. "We will look at all kinds of measures ... That is the most important thing we can do" to ensure the benefits of the recovery are more fully shared.

Markets were little changed over the course of the hearing.

Powell's comments were "not really much that we haven't heard before," said Michael Brown, a senior analyst at payments firm Caxton, London.

A SENSITIVE PIVOT

But the session, at times a sparring match between Democrats and Republicans over the Biden administration's economic plans, hinted at the delicate line the Fed must walk in coming months as it balances inflation risks with its promise to ensure the economy recovers all the jobs lost after the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell testifies during a U.S. House Oversight and Reform Select Subcommittee hearing on coronavirus crisis, on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., June 22, 2021. Graeme Jennings/Pool via REUTERS

Until recently there was little perceived conflict between those goals.

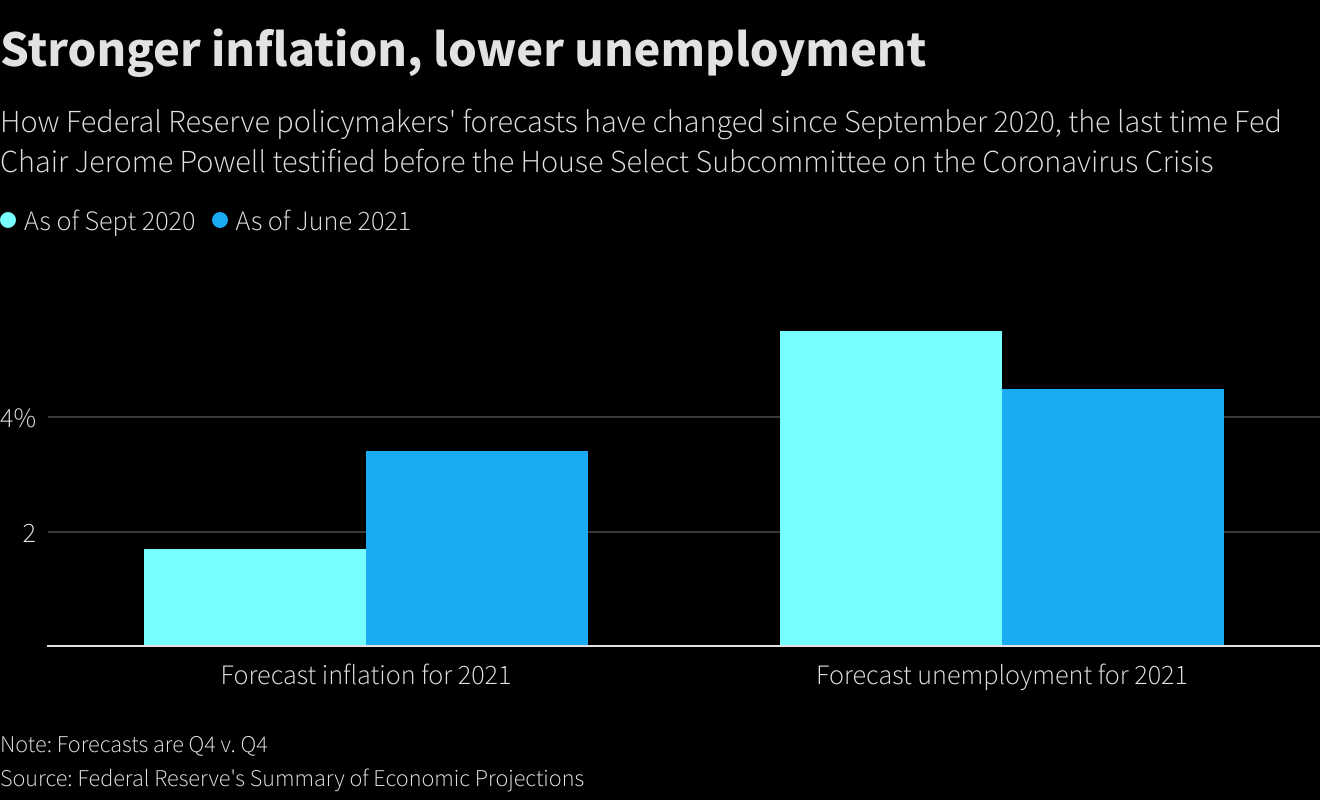

Yet since Powell last appeared before the subcommittee in September, the central bank's outlook for inflation has doubled. Projections released by the Fed last week showed prices in 2021 are expected to increase at a 3.4% rate, compared with the 1.7% projected as of last September.

Recent job growth, meanwhile, has been slower than hoped. Some of Powell's colleagues are now openly suggesting the pandemic prompted so many people to retire it may be unrealistic to think the United States can return to the pre-crisis level of employment before the Fed needs to tighten monetary policy.

That is a stance counter to Powell's own focus on restoring the economy to the conditions of early 2020, and to that of the subcommittee's influential Democratic chairman, Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina, who pushed Powell on Tuesday to ensure a fair and equitable jobs recovery.

"Millions of Americans are depending on the Fed to continue to support the economy’s recovery,” said Clyburn, who has close ties to President Joe Biden.

Biden must decide in coming weeks whether to reappoint Powell to a second four-year term. In the closing minutes of the hearing the Fed chair received a glowing review from another ranking Democrat, House Financial Services committee chair Maxine Waters of California.

Waters noted that Powell was ready to "think big" about policy as the pandemic took hold and said she wanted to thank him "not only for his leadership ... but his creativity."

Still, a rapidly improving economic landscape is beginning to reshape views at the Fed about when to reduce some of those pandemic efforts as the crisis recedes.

At their meeting last week Fed officials projected they may raise interest rates as soon as 2023, perhaps a year earlier than anticipated, and Powell said during a news conference that the central bank was beginning talks about when to pare down its $120 billion in monthly purchases of government bonds and securities used to support the recovery.

Powell told reporters the economy "is still a ways off" from the progress in rehiring that the Fed has said it wants to see before making any changes, a cue that the timing of an actual policy shift remains up in the air.

But the change in tone and projections surprised markets, which are now keenly watching to see if the Fed is hedging its job market promises.

Market trading in inflation-protected and other securities shows investors betting the Fed will raise rates even faster than policymakers project, a potential loss of faith in the central bank's willingness to run a "hot" high-inflation economy to encourage a robust jobs recovery.

This article originally appeared on Reuters.