This question is one investors should consider as the Fed does “whatever it takes” to battle the corona-virus pandemic.

The Fed’s announcement on March 23 that it would reinstate programs launched in the 2008 financial crisis and expand upon them set off a huge market rally. Yet, by the Fed’s own admission the challenges it faces in bolstering the economy are considerable.

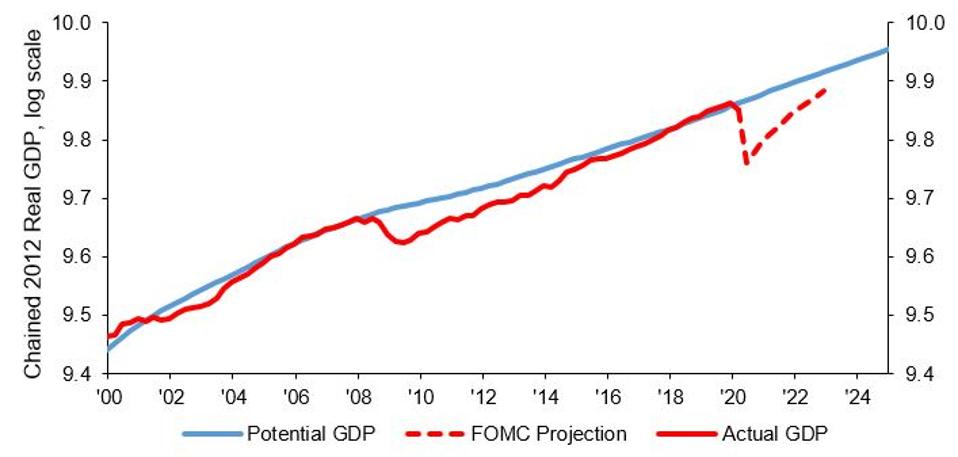

As shown below in a chart created by Stephen Cecchetti and Kermit Schoenholtz, the latest forecasts of FOMC members see the economy operating well below its potential over the next two years. In the press conference after the FOMC meeting, Chairman Powell emphasized that “We’re not thinking about raising rates. We’re not even thinking about thinking about raising rates.”

Figure 1. U.S. Real GDP: Actual, Potential and FOMC Projections

Note: We estimate 2Q 2020 real GDP by taking the average of the latest nowcasts of the Federal ... [+]

SOURCE: CECCHETTI AND SCHOENHOLTZ, FEDERAL OPEN MARKET COMMITTEE, FORT WASHINGTONWhy then are investors so confident?

One explanation put forth by Mohamed El-Erian is investors believe they can take advantage of a “win-win” situation: The stock market will do well if the Fed’s forecast is too pessimistic, and if it proves accurate, the prospect of low interest rates for the foreseeable future will prop up the market.

Nonetheless, there are several risks to consider. One is that cases of corona-virus in the U.S. have come down much less than in Asia and Europe because the U.S. response to the pandemic was slow and erratic. What weighs on Fed officials is the possibility of a second wave that could hinder the re-opening of businesses.

This scenario is not the baseline for the Fed forecasts. But policymakers understand it is difficult to assign probabilities to various outcomes because the circumstances today are completely unprecedented. Normally, this would make people cautious about the future.

As with previous crises, the Fed’s actions are intended to lessen tail risks. One handicap the Fed faced this time was interest rates were already near record lows. Because its room for maneuver was limited, it took interest rates to zero very quickly.

At the same time, the Fed began large purchases of U.S. treasuries and mortgage backed securities, and for the first time announced it would also purchase corporate bonds. These actions boosted the size of the Fed’s balance sheet from $4 trillion to $7 trillion, which helped fuel the stock market’s surge. The commonly cited explanation is the injection of liquidity into the financial system would find its way into stock purchases.

This begs the question about how the transmission mechanism works. Just before he stepped down as Fed chair in 2014, Ben Bernanke was asked if he was confident that quantitative easing (QE) would work. He replied: “The problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.”

Bernanke was alluding to the first round of QE launched in 2009, which succeeded in stabilizing financial markets and lessening the risk of a full-blown credit crunch. However, the next three rounds were less effective and the economic expansion was subpar.

So, why do investors think QE will be more effective in bolstering growth now?

In my view, some take it as a given that Fed balance sheet expansion will automatically boost the money supply. But this presumes that banks will lend the funds that are deposited; if not, they will sit on bank balance sheets as excess reserves.

Recognizing this, the federal government launched new programs such as PPP and the Main Street lending program to create incentives for banks to backstop small and medium size businesses. At this juncture it is too early to tell how effective these programs will be. However, Edward Altman of NYU expects the number of large bankruptcies will challenge the record set after the 2008 financial crisis.

The bottom line is there is more compelling evidence the Fed can influence financial markets via QE than impact the economy or corporate profits. The risk, therefore, is the stock market could become vulnerable if the economy does not meet expectations.

In these circumstances many have adopted the mantra “Don’t fight the Fed!” However, they would be well served to consider another caveat – “Buyer beware.”

This article originally appeared on Forbes.