(MarketWatch) A price rally in the 10-year Treasury note pushed yields on Tuesday to around a fresh three-year low, while the German bond has been carving out record lows almost daily. And some estimates peg the amount of government debt swirling around the globe bearing yields below 0% at about $17 trillion.

But don’t call this a bond bubble, according to Neil Shearing of Capital Economics.

The group’s chief economist, in a research note dated Sept. 3 titled “No, this isn’t a bond ‘bubble,’” said the “uncomfortable truth” about the surge in global bond prices, which rise as yields fall, is justified by economic conditions.

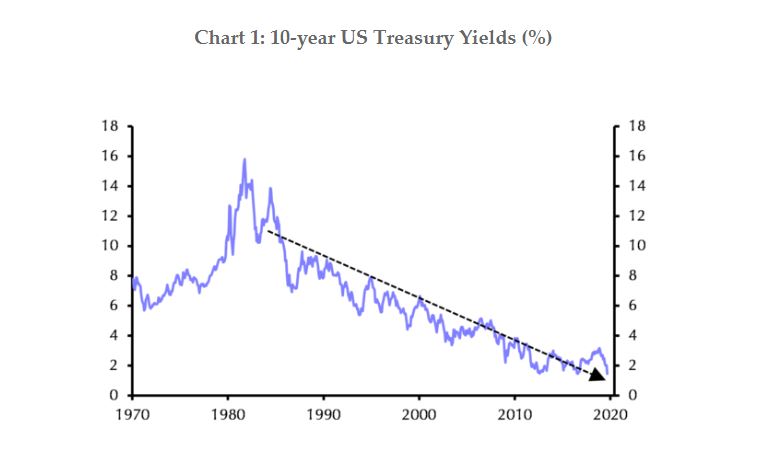

Shearing makes the case that the so-called nominal yield — which refers to the coupon or rate that a bond pays the holder — of government debt boils down to two things: “expectations for short-term real policy rates over the life of the bond and expectations for inflation. These feed off one another, and both have fallen sharply over the past 30 years.”

The economist said structural and demographic changes in past decades, including stubbornly low inflation, which affect real yields, and aging populations in the developed world, as well as skittishness to invest by emerging markets in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, have increased the appetite to save and decreased capital investments.

Shearing said that further easing by central banks to stave off the impact of a slowing global economy could reduce the desire to save because returns on borrowings will be scant as compared with investing, but it isn’t clear that that will have the desired effect of driving inflation toward the 2% target of most developed economies— and bursting the bond bubble.

“In particular, a consensus in favour of looser fiscal policy could both reduce desired savings and increase desired investment — thus pushing up both real and nominal interest rates and bond yields. But while we wouldn’t rule this out, there’s not much evidence of it happening imminently,” he wrote.

On Tuesday, the 10-year Treasury note yield fell 3.4 basis points to 1.469%, its lowest since July 2016, after the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index for August fell to a reading of 49.1, its lowest level since January 2016.

Worries about a recession domestically and abroad have at least partly helped to stoke appetite for bonds, while knocking around major stock markets, like the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 index.