(Forbes) Sorry haters, Putin’s securities market is better than Xi’s, better than Trump’s. It’s Europe’s fault.

For all the talk about starving Vladimir Putin and, inevitably, Russia of financial resources with sanctions on major state-run companies, Russian bonds have become a must have. Not only in Europe where yields are nearly zero, but also among American global bond fund managers that want to get paid for holding debt.

Considering there is about $15 trillion worth of negative yielding bonds out there, Russia’s 10-year sovereign looks great to everyone, except to the most scorned of the anti-Russia crowd, at around 6.4% in rubles.

Russia’s 2027 dollar-bond pays 4.25% interest. Germany doesn’t pay at all, and instead yields -0.35%. The U.S. 10-year Treasury bond yields just 1.8%. Those countries also have debt burdens that can spook long-term investors. Russia has practically no debt at all.

“They’ve made themselves bullet proof,” says James Barrineau, co-head of emerging market debt for Schroders Investment in New York. “They can pay off all their foreign debts with their central bank reserves. Plus, they’re cutting interest rates. The currency is very stable. And they have room on the fiscal side to spend on their economy.”

Russia has over $433 million in foreign currency reserves and $107.9 million worth of gold. It is the largest reserves among the big emerging markets after China, which has more than $3 trillion.

Ridiculously low interest rates on European government bonds, and higher dividends being paid by Russian companies, has investors overweight Russian securities.

Here are some of Russia’s most well-known dividend paying stocks:

Retailer Magnit’s dividend yield is a whopping 8.62%. Its competitor X5 Retail Group pays 4.15%.

Lukoil, a privately owned oil company that even has gasoline stations in New York, pays 5.05%. Their stock price is up 39% this year.

Telecommunications giant, Mobile TeleSystems (MBT), which trades on the NYSE, pays 5.7%. MBT is up 26.4% year-to-date.

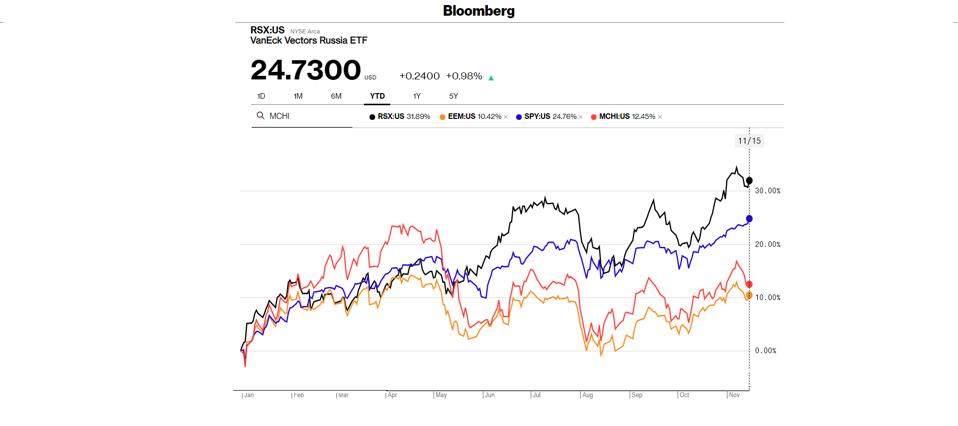

The VanEck Russia (RSX) pays 3.91% in dividend yield as of November 15.

Russia’s break from the Soviet Union came with at least three financial crises, each one either delivering a – temporary – crushing blow. Since the break up of the USSR, many of Russia’s wealthy have left or hid money offshore while the country still faces somewhat of a brain drain. Russians in the science and engineering fields are working in the U.S. and Western Europe instead. All of this, coupled with lackluster demographics, stagnant oil and gas prices and U.S. sanctions, have been a big negative for Russia.

Russia is used to negatives.

The 1995 banking crisis that led to the 1998 financial meltdown saw the domestic investor give up on the idea of investing in stocks and bonds. Capitalism was a failure to them.

A few years later, they turned to real estate, building a Chinese-style housing bubble that popped in 2008 and never recovered.

Eleven years on and Russian real estate prices are almost 60% lower than they were at their market peak in dollar terms. Plus the currency is much weaker ever since Central Bank governor Elvira Nabiullina took the ruble out of its strict trading band against the dollar. It used to trade in the 30s. Now it’s in the 60s.

Since real estate is no longer offering Russians the returns on investment in once did, those that don’t have enough capital to open up accounts overseas, or need to keep money at home, are rediscovering the stock market.

This slow, but sustained development of trust was partly the result of time, and partly the result of a number of more fundamental changes taking place within Russian securities law.

Since 2007, the number of retail clients registered with the Moscow Exchange has gone up 120%.

Legislation protecting investors was improved. A deposit insurance system was created. Savings banks institutionalized and professionalized thanks in large part to foreign competition from Europe and the U.S. Russian banks were subject to tighter rules, exactly like those of Western banks. Those that were not up to speed, either failed or were taken over by the Russian Central Bank. Russia’s banking system may look smaller than it did a few years ago, but it’s getting cleaned up.

Since 2016, retail investors are facing a problem of gradually falling savings deposit rates. In real terms, savings deposits now return less than 2% per year.

So while Russian bonds have been made “bullet proof” thanks to negative yield in Europe and Russia’s low levels of foreign debt given bond investments their repayment confidence, Russia’s stock market is beefing up because the locals are running out of places to put their money.

Just as with real estate, the shift to a new investment is coming. Equities are it. Good returns over the last 12 months will entice more investors to jump in, driving up Russian stock prices.

Russian GDP is expected to grow by just under 2% next year.

“A major change in the Russian financial sector over the last couple of years has been the simultaneous rise in the dividend yield of Russian stocks and the fall in the yields offered by government and corporate debt, and retail deposits,” say Roland Nash and Denis Rodionov, analysts for Moscow and London-based investment manager Spring Capital, writing in a report to clients this month. “The impact of this change will likely be greater interest from domestic investors in holding equities.”