(Reuters) Tens of trillions of global investment dollars are pouring into companies touting robust environmental, social and governance credentials. Now short-sellers spy an opportunity.

Such hedge funds, often cast as villains of the piece because they bet against share prices, scent a profit from company valuations they believe are unduly inflated by ESG promises or which they say ignore risks that threaten to undermine the company’s prospects.

The fact short-sellers, who look to exploit information gaps, are targeting the ESG sphere underlines the complexities facing investors in accurately gauging companies’ sustainability credentials. Teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg last week spoke of CEOs masking inaction with “creative PR”.

Against a backdrop of growing public and political concerns about climate change and economic inequality, companies are under increasing pressure to show they are taking greater responsibility for how they generate their profits.

Investments defined as “sustainable” account for more than a quarter of all assets under management globally, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. About $31 trillion has been invested, buoyed by analyst reports that show companies with strong ESG narratives outperform their peers.

Some short-sellers, including Carson Block of Muddy Waters, Josh Strauss of Appleseed Capital and Chad Slater of Morphic Asset Management, argue share prices can be bolstered by corporate misrepresentation about sustainability, or so-called “greenwashing”.

“Greenwashing is absolutely rampant now,” says Slater, whose fund bets on both rising and falling share prices. If companies fail to engage with long-term investors, he sees a red flag.

“From the short side, it’s quite interesting.”

Analytics companies that provide corporate ESG ratings use a combination of company disclosures, news sources and qualitative analysis of third-party data. They are a major source of information for investors, but it is not an exact science.

Hedge funds have various strategies for selecting targets, often focusing on those they think show both ESG and more traditional financial or operational weakness. A high ESG rating can attract short interest.

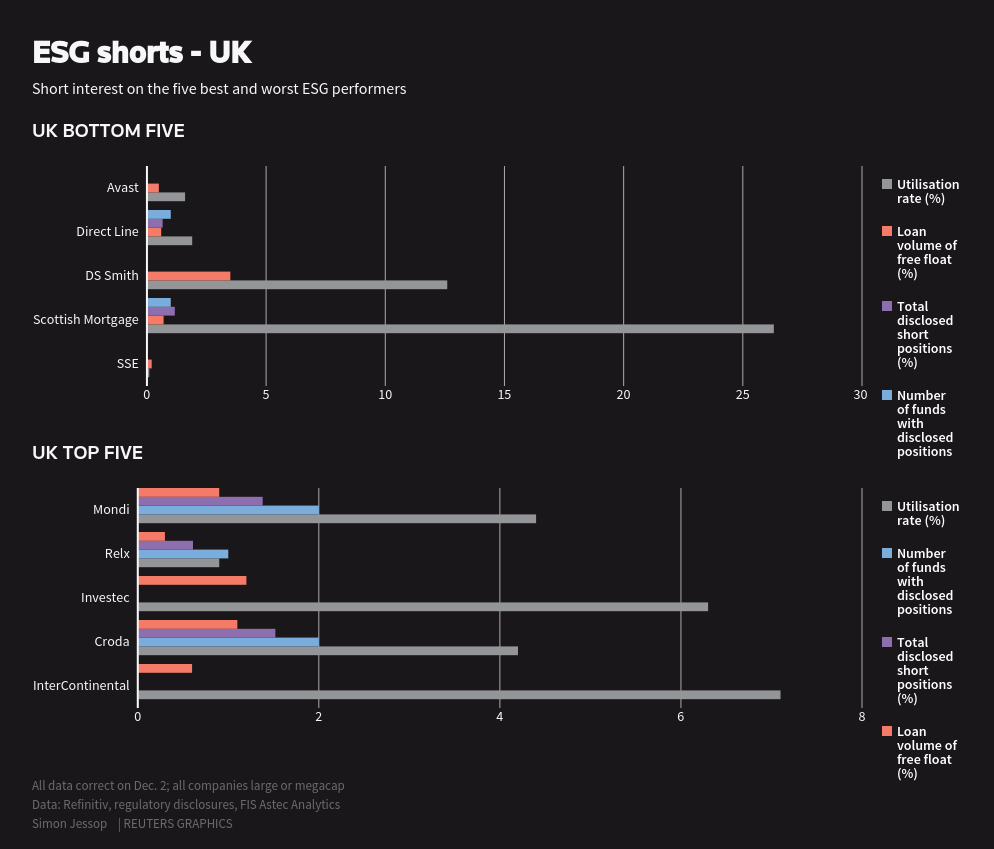

A Reuters analysis of data from financial information company Refinitiv and national regulators in Britain, France, Germany, Spain and Italy shows the five companies in each country with the best ESG scores collectively were being shorted more than those with the worst scores.

The short positions against the companies deemed to have the best ESG credentials were 50% greater in size than those placed against the worst-performers.

(Graphic: ESG shorts - UK: here)

For an interactive version of the graphic, click here tmsnrt.rs/2RwpBDj. For additional graphics covering the other countries mentioned, see related content.

PATCHY DATA

ESG data providers compile ratings based on a slew of measures ranging from energy usage to board gender make-up, salary gap data and the scale of negative press reports on the company from newspapers across the world.

Refinitiv, part-owned by the parent company of Reuters News, factors in more than 400 ESG measures for each company, taken from a range of sources including company reports, regulatory filings, NGO websites and news articles.

A key problem, though, is scant regulations governing what ESG measures and risks companies must disclose and their patchy nature, said Diederik Timmer, executive vice president of client relations at Sustainalytics, a major ESG data provider.

“When things go well, companies report quite well on those, when things don’t go so well it gets awfully quiet,” he added.

Some policymakers, largely in Europe, are pushing for standardized disclosures to help investors better gauge the risks, something which will leave less wriggle room for companies and make scores even more reliable.

Two leading global asset managers interviewed by Reuters, who manage nearly $1 trillion in assets but declined to be identified, said they had tested their portfolios using several data providers and found the correlation between ESG ratings to be so low, they are building their own ranking system.

Peter Hafez, chief data scientist at RavenPack, which helps hedge funds analyze data to get a trading edge, agreed.

“There’s no perfect ESG rating out there,” he said.

The influence of news flows on investor sentiment was underlined by a Deutsche Bank study here published in September that mapped 1,600 stocks and millions of company announcements and climate-related media reports over two decades.

It found companies that had a greater proportion of positive announcements and press over the preceding 12 months outperformed the MSCI World Index by 1.4% a year, on average, while those with more negative news underperformed by 0.3%.

BIG RISKS FOR SHORTS

Short-sellers borrow shares, pay the lender a fee and sell them on, betting the price will fall before buying them back and returning them to the original lender - pocketing the difference, minus the fee.

But it is not for the faint-hearted. If funds trigger a share price fall, they can earn millions, but the downside, should shares rise, is unlimited.

The perils of the practice were shown by the shorts burnt by a 17% surge in the shares of Elon Musk’s Tesla (TSLA.O) in October after a surprise quarterly profit. Short-sellers suffered paper losses of $1.4 billion, erasing most of their 2019 profits, according to analytics firm S3 Partners.

And in a decade-long stock market bull-run, short-selling can be tricky.

Morphic’s joint chief investment officer Slater said the Sydney-based money manager’s standalone short positions in its Trium Morphic ESG long-short fund had weighed on the portfolio over the past 12 months.

Niche activist short-sellers, who can torpedo company valuations by publishing negative reports on targets - often alleging fraud or serious failures - are often criticized for undermining long-term company objectives and blurring the lines between whistleblower and market manipulator.

Short-sellers agree they are biased, but argue no more than long investors, the banks that raise money for the company and the company’s management.

Carson Block, founder of American short-seller Muddy Waters, who shot to prominence spotting wrongdoing in some Chinese-run companies, is now seeking a “morality short” on ESG - branching out from a traditional focus on corporate governance issues to targets whose success he says hinges on secretly harming society.

As an example of what he is seeking, he points to the U.S. opioid crisis, which has triggered around 2,500 lawsuits by authorities seeking to hold drugmakers responsible for stoking a scandal that has claimed almost 400,000 overdose deaths between 1999 and 2017.

“I’m really skeptical of ESG,” he says, likening the use of the acronym by the corporate world to the token straw slipped into a large plastic cup with a plastic lid.

“ESG is the paper straw of investing,” he says. “I definitely want to find companies like that because I know they’re out there and I want to help put them down.”