U.S. banks have long looked with pity at overseas lenders coping with negative interest rates. Now, they’re grappling with the fear they may join the crowd.

Negative rates -- especially if they persist for many years -- reduce the spread banks make between lending and borrowing because they cannot pass the negative rate onto most depositors. Coupled with surging defaults due to an economic downturn, they can sap profits out of the banking system even if they create an initial jump in lending. That toxic combination has crippled Europe’s banks in the last six years, a dreaded position their U.S. peers would like to avoid.

“Initially, there’s a sugar rush when negative rates are introduced,” said Alberto Gallo, head of macro strategies at London-based hedge fund Algebris Investments. “But ultimately, over time, you zombify the banks by lowering the velocity of money. Negative rates are a bad idea.”

Surging provisions for bad loans have already eaten into U.S. bank profits, with the top six firms seeing their first-quarter income decline by about 60%.

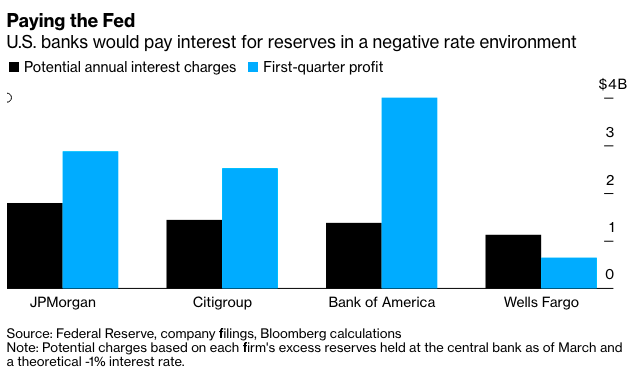

A quarter-point cut to zero for the upper bound of the Fed’s main policy rate could lower annual income by about $1 billion to $2 billion for each of the biggest banks, according to their latest quarterly filings. Further cuts below zero would add additional costs: paying the Federal Reserve for the $3 trillion excess reserves held at the central bank. At a hypothetical -1%, that would mean an annual charge of $30 billion for U.S. lenders, and roughly $10 billion of that would fall on the six biggest firms.

Fed policy makers have pushed back on traders who are pricing in the chance that they utilize a negative-rate policy. Earlier this month implied rates on Fed-funds futures showed traders saw likely odds of the central bank cutting rates below zero in January. Prices have stabilized since with futures no longer pricing in a negative Fed rate, yet options traders continue to purchase contracts that hedge against risk of that happening.

“Debt traders and the stock market overall are still pricing in the idea of negative rates being part of the arsenal of what the Fed may do,” said Patrick Leary, chief market strategist and former trader at independent broker-dealer Incapital. “My mantra on the Fed, particularly this Fed, is don’t look at what they say. Look at what they do -- and look at what the market tells them to do.”

Bank executives constantly decry negative rates, arguing that the benefits to the economy are elusive while the harm to the banking system is significant. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon has talked about “huge adverse consequences” of negative rates. European banks, which have suffered on their home turf with below-zero rates since 2014, have warned U.S. policy makers not to follow suit.

“Please don’t do this,” said Christiana Riley, head of Deutsche Bank AG’s U.S. operations, at a conference in October. “It defies all logic.”

Still, President Donald Trump has consistently pressured the Fed to go negative, recently calling it a “gift” to the U.S. economy that should be accepted.

The biggest U.S. banks are still counting on Fed Chairman Jerome Powell not to heed those calls. In their latest quarterly filings, the scenarios that look at the potential impact of interest-rate changes on income all assumed a zero floor in the U.S. while considering lower rates worldwide.

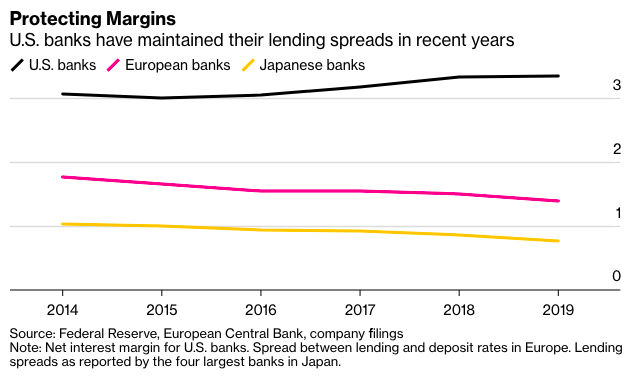

Nevertheless, the banks are running internal models with negative rates, executives say. While they won’t reveal the numbers, executives acknowledge that the drop in income would grow incrementally as rates went further and further below zero. European lenders’ interest margins have declined by more than a quarter since the European Central Bank went negative, starting with -0.1% in 2014 and ending last year at -0.5%. Margins in Japan have dropped by about the same since 2016 after the Bank of Japan went to -0.1% and stayed there.

Algebris’ Gallo says U.S. banks have more pricing power in lending than their European counterparts because the banking system is dominated by a few large companies, which should cushion some of the blow from negative rates, at least initially. Most loan contracts in the U.S. have zero-rate floors even if they’re pegged to market interest rates, executives say. The largest U.S. lenders also earn quite a lot more than European peers from capital-markets businesses after having gained share in recent years.

Despite all the push-back, the Fed might move rates below zero if the right conditions unfold, according to JPMorgan analyst Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou. Those include the market ramping up its wagers again for negative rates and other leading central banks that haven’t gone negative yet switching tracks to do so, Panigirtzoglou said. In the short run, that would be a good move, though the benefits would erode after a year or two, he said.

“Negative Fed policy rates should help liquidity in the banking system as reserves should start propagating rather than staying idle at the big banks, which have been hoarding them,” said Panigirtzoglou, a London-based global market strategist. “For some smaller banks there are shortages of reserves and they’ve had to pay higher rates in the interbank market to get liquidity.”

While the Fed hasn’t yet delved into the sub-zero policy-rate zone, Treasury yields of the shortest of maturities have traded negative before and currently those with tenors out to two years have rates below the 0.25% top of the central bank’s target range. Two-year notes yield 0.17% and four-week Treasury bills are at just about 6 basis points. From mid-March to early April the four-week bill rate was mostly negative, in part due to shortages of the security.

“Market rates are so close to zero, negative rates are no longer a far-fetched scenario for U.S. banks,” said Brian Kleinhanzl, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods based in New York. “The longer they last, negative rates are a slow burn on net interest margins. Coupled with bad credit, that would permanently impair their business models just like it did European peers.”

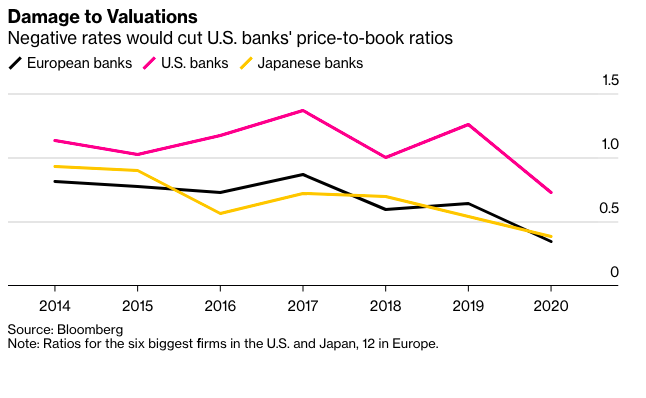

Several years of negative rates would probably bring market valuations of U.S. banks to levels European and Japanese rivals have faced for a while, Kleinhanzl said.

This article originally appeared on Bloomberg.