Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recognizes that he can’t prevent what increasingly looks like a sudden stop of the U.S. economy, but he’s still hoping to avoid a freezing up of financial markets that makes the pain even worse.

In a roughly 40-minute conference call with reporters on Sunday after the Fed slashed interest rates close to zero and launched a fresh quantitative easing program, Powell acknowledged the economy is set to contract in the second quarter as companies and households hunker down to hinder the spread of the deadly coronavirus.

And he said how long the downturn lasts is “unknowable” because it depends on how the contagion develops.

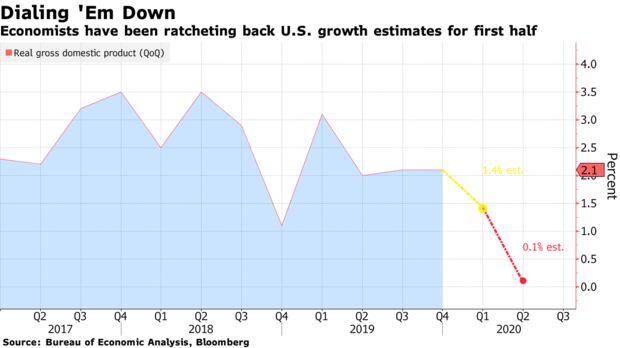

“We’ve hit a wall. The economy is in free-fall,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, who reckons that gross domestic product will shrink at a jaw-dropping 5% annualized rate this month as business comes to a standstill.

What the Fed is focused on first and foremost, Powell said, is providing liquidity to financial markets so they can function smoothly and supply credit to companies and consumers to tide them over during the fallout from the virus and the necessary distancing actions taken to contain it.

That’s a tacit acknowledgment that sharp rate cuts alone are insufficient to spur demand and stabilize the current economic emergency, but may help drive a rebound once the virus is under control.

“We’re really going to be looking to see that financial markets are returning to more liquid, more normal functioning,” Powell said. “We take that job very seriously. It’s probably the most important thing that we’re doing now.”

Despite the Fed’s multi-pronged approach, U.S. stock futures tumbled and Treasuries rallied on Monday as investors continue to question whether the Fed has done enough to ease a credit crunch, keep markets flowing and avoid a lengthy recession.

That shows there is a lot at stake. While the efforts to contain virus will have, in Powell’s words, “a significant effect on economic activity in the near-term,” whether that metastasizes into a prolonged downdraft depends in part on the what policy makers in response, including whether they succeed in avoiding market dislocations.

“The task at hand for governments and central banks has been and continues to be to ensure that the recession stays relatively short-lived and doesn’t morph into an economic depression,” Joachim Fels, global economic adviser for Pacific Investment Management Co., said in a report Sunday to clients.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists now expect the economy to stagnate this quarter and shrink 5% in the subsequent three months. But they expect recoveries of 3% and then 4% in each of the next two quarters.

Besides the 100 basis-point rate cut and $700 billion QE program, the Fed reduced rates on its discount-window loans to banks and on its dollar swap lines with major foreign central banks. It also did away with commercial bank reserve requirements, freeing up what some analysts reckon is close to $150 billion for potential loans, as part of a surprise Sunday package.

Other central banks also acted Monday. Those of New Zealand and South Korea cut rates, while the Bank of Japan boosted asset purchases and others sought to keep markets liquid.

President Donald Trump, who has been relentless in his criticism of the Fed, welcomed Sunday’s moves.

“It makes me very happy and I want to congratulate the Federal Reserve,” he said. “That’s a big step and I’m very happy they did it.”

With interest rates now effectively at zero, many economists -- and seemingly Powell himself -- believe that it’s essential that Trump and Congress weigh in with more measures to support demand -- just as happened in the 2008-09 financial crisis. Trump and fellow Group of Seven leaders are set to discuss the crisis by teleconference later Monday.

“We do think fiscal response is critical and we’re happy to see that those measures are being considered,” the Fed chair said.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said on Sunday that an $8 billionemergency spending bill and a House of Representatives-passed economic relief plan for households are only the first two innings of a nine-inning baseball game.

“We have a lot more we need to do with Congress,” Mnuchin said. “We will make sure the economy recovers.”

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...

“The Fed’s actions are aimed at the immediate objective of preventing a breakdown in financial markets, and the longer term objective of preparing the economy for the fastest-possible post-outbreak recovery.”

--Carl Riccadonna, Yelena Shulyatyeva, Andrew Husby and Eliza Winger

See more here

Powell argued that the Fed also has more tools to wield to aid the economy, including forward guidance on the future direction of short-term interest rates and more asset purchases. He did though seem to rule out taking rates negative -- a tactic that other major central banks have employed.

“The Fed is now effectively out of the picture,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief U.S. economist Michael Feroli told clients. “They did what they could do but they can’t do much more.”

Fed watchers said the central bank may need to go further in its efforts to achieve what Powell suggested was its primary goal at the moment -- keeping the markets functioning and credit flowing -- though it’s not clear it can do that on its own.

Besides buying Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, some economists think the Fed should set up emergency lending windows as it did during the financial crisis to support specific segments of the market, such as commercial paper, which provides critical short-term financing for many businesses.

“The market is in effect saying cutting rates to zero and restoring market functioning in Treasuries and MBS is a necessary but not sufficient condition for restoring credit supply to households and businesses,” Krishna Guha, head of central bank strategy at Evercore ISI, said in an email.

Powell left the door open to further action on that front, though he also seemed to acknowledge that there was a limit to what the Fed could do.

“We don’t have the tools to reach individuals, and particularly small businesses,” he said.

Megan Greene, an economist and senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, agreed.

“When it comes to directly supporting households and small and medium-sized enterprise facing a temporary sudden halt in income, fiscal policy needs to carry the weight,” she said. “So far the fiscal measures on the table are woefully insufficient, and until Congress does more and a natural peak for the coronavirus emerges, the markets are unlikely to find a bottom.”

This article originally appeared on Bloomberg.