If there is one fear that seems to constantly haunt investors, it is that latent inflation flares up and flattens markets. Most central banks in developed economies look to target a 2% inflation rate and have, over the last several decades, succeeded in anchoring investor expectations.

With unprecedented stimulus stoking the global recovery, concerns are taking hold that inflation dynamics are about to shift. Higher costs from dislocated supply chains, a reduced service sector and pent up demand as vaccine adoption crests will likely pressure prices. However, many of these factors may be transitory. Once the economy adjusts to any new constraints, price pressure will likely moderate.

The biggest threat to financial normalization may be swelling government debt and the money printing that is helping monetize it. Could this debt buildup and related deficit spending push inflation and rates significantly higher?

Lessons From Japan

Japan is an advanced case of a developed country with an outlier debt to GDP ratio, yet inflation has been moderate for decades and its currency remains a safe haven.

Adam Posen, Head of the Peterson Institute and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, has concluded from his decades of research that sustainable debt is more a function of a country’s ability to tax.

Posen argues that for inflation to take off, debt monetization has to make its way into credit growth and create demand that significantly outstrips supply. Therefore, printing money to buy government debt is unlikely to fire up inflation, unless demand overwhelms supply and investors lose confidence and dump the currency.

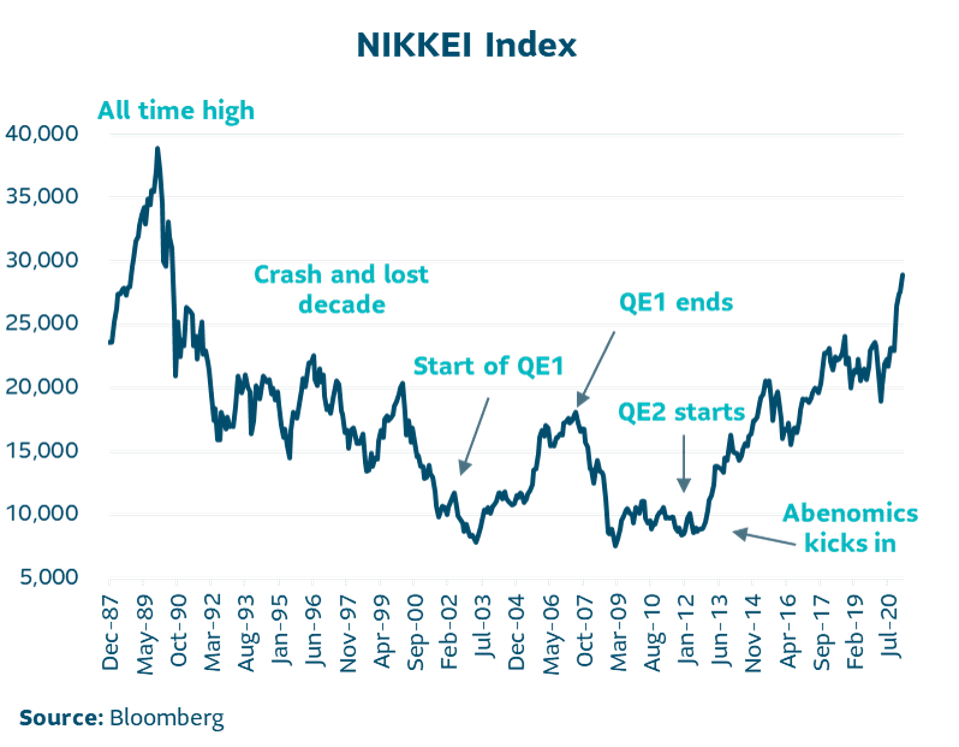

In the 1990s, after the property and stock market crash in 1989, Japan’s fiscal and monetary policy was tame, resulting in anemic growth. But in 2001, Japan shifted to an unprecedented Quantitative Easing (QE) program that they let fizzle out in 2006. By 2010 it was resurrected, and in 2012 turned up several notches when Shinzo Abe became Prime Minister. He combined an ambitious program of fiscal, monetary and structural policies to accelerate the recovery. It worked.

While Japan’s per capital GDP was the lowest amongst G-7 peers from 1990-2002, it was the third highest after that, and also delivered the second highest productivity growth rate. Without massive QE, Japan would have been trapped in secular stagnation, as was confirmed by the lagging growth of the 1990s. Through a succession of QE programs, growth was revived.

The path of the stock market (Nikkei 250) captures the recovery as investor confidence and monetary policy gained traction and the market cheered.

The key lesson from Japan is that significant monetary force made a difference and restored confidence that the debt would be covered by sustained economic growth. Indeed, one of Posen’s main conclusions is that over the last two centuries wealthy democracies have generally succeeded in preventing capital flight. In contrast, loss of investor confidence has been the hallmark of some of the notable currency meltdowns and inflation spikes in some emerging markets.

Corrosive Inflation Is Fairly Rare

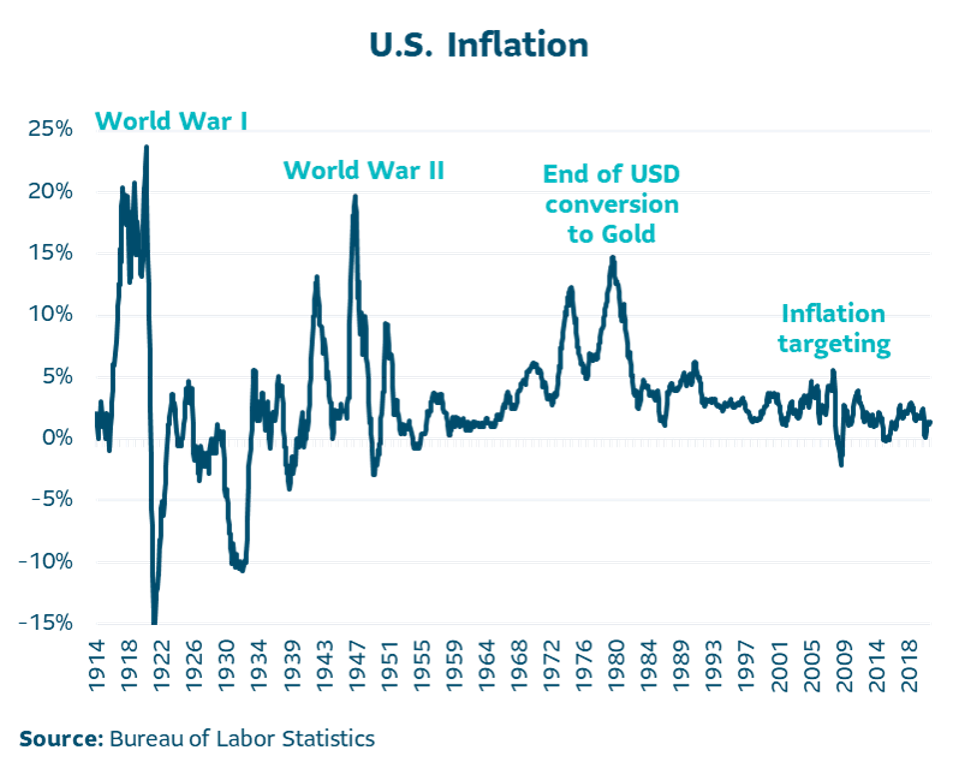

Inflation is chiefly a modern phenomenon. Researchfrom Jim Reid, Head of Global Fundamental Credit at Deutsche Bank, finds that inflation was fairly contained and rare before the twentieth century.

Meanwhile over the last century, the U.S. has had three major episodes. This includes the two World Wars and their aftermath, as well as the 1970s, when the U.S. broke its link to the gold standard and an overly politicized Federal Reserve (Fed) abandoned monetary independence

However, under new leadership, the Fed restored credibility, overcame stagflation and launched a new chapter of inflation management that continues to this day. So it’s worth remembering that significant inflation has been relatively novel and that central banks have had notable success in anchoring inflation.

So Where Do We Stand Right Now?

Market expectations of inflation over the next five years point to topping at 2.5% and ultimately settling around 2% longer term. This is exactly what the Fed is aiming for – a near term overshoot with an eventual return to target. At this point the Fed and the market seem in sync.

While inflation expectations tend to be a forward view, they can be influenced by current effects, particularly changes in oil prices. As recovery takes hold in the coming quarters, there will undoubtedly be some inflation scares as pent-up demand kicks in and activity ramps up.

So, the essential question is whether the post-vaccine era will structurally force inflation higher. The quick answer seems to be that we are unlikely to see a sustained surge in inflation expectations. After all, many parts of the labor market still have an arduous road to recovery. If wage inflation starts to pinch, companies can increase automation, something they have neglected for years.

Certainly, some supply chains will be reordered. But for sophisticated processes, it will take time. Many were optimized over decades and require sizeable capital outlays to replicate. Therefore, any significant transition of capital-intensive supply chains will be gradual.

And finally, there is the Fed. Over the last few decades, they have gained credibility in anchoring inflation. They have aggressively used quantitative easing to mitigate significant shocks and avoid deflation. With central banks everywhere on the same cycle, the debt build-up may only become a vulnerability if a country’s growth materially lags peers.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.