El Salvador’s decision to recognize bitcoin as legal tender is confusing for the majority of people who still see the cryptocurrency as a speculative bubble or a Ponzi scheme.

The arguments against such adoption are, seemingly, quite logical.

Bitcoin’s price is volatile–on May 19, for example, it plummeted 23% in two hours–so it appears to fail the most basic test of any currency: acting as a “store of value”.

This, in turn, hinders its ability to serve as a “unit of account”–another key test. Retailers cannot price their goods in BTC, as those prices would need to be changed continuously throughout the day. And even then, the “real value” of the goods would still be pegged to a more stable unit of account, such as the US dollar. If the price of an apple went up in BTC terms, that would tell you nothing about the value of apples; it would simply mean that bitcoin is having a bad day.

Critics see a host of problems here. Sure, El Salvador can pass laws that force its retailers to accept bitcoin. But lots of governments try to force citizens to do things they don’t want to–and citizens invariably find a way out. In a predominantly cash economy like El Salvador, the way out is obvious. And what about those high transaction fees? Why would anyone buy a $1 newspaper with bitcoin, when the cost of engaging with the network is often about $10?

If there’s one mistake that bitcoin enthusiasts make when hearing these concerns, it’s being dismissive.

Far better to acknowledge the criticism; admit that bitcoin is an immature asset with room for improvement; and explain why some of those improvements are closer than many people think. Close enough, even, to bear fruit in 2021.

Let’s start by considering how a bitcoin standard can improve lives in El Salvador. It’s model that can and probably will be replicated across the developing world, triggering the largest shift in global wealth creation for centuries.

Got corn?

To understand how El Salvadorians engage with their economy, we need some basic economic data for the country.

First and foremost: it’s poor. Real GDP per capita is just $8,891, according to the International Monetary Fund, which is less than $25 per person per day. Every penny counts. Another important point: about one-fifth of the money flowing through the economy is sent to El Salvador from citizens living and working overseas. These remittances are a lifeline for the country. They totaled $6.8bn over the past 12 months, according to the Central Reserve Bank of El Salvador.

So what can bitcoin bring to the party? Two things. In the short-term, it can ensure that more of these remittances go to their intended recipients, instead of being siphoned off by intermediaries. Longer term, it can also give El Salvadorians the chance to hold a currency that is designed to appreciate in value over time, instead of depreciating.

The short-term argument is incontrovertible. Money-transfer companies like Western Union WU -0.2%, WorldRemit and Xoom charge fees to send cash across borders. They’re businesses providing a service, after all, and they need to get paid. Impoverished El Salvadorians are the ones paying them–perhaps $440m per year, given the global remittance sector’s average fee of 6.5%. Bitcoin’s network fees are much lower.

The longer-term perspective, though, is hard for many to conceptualize.

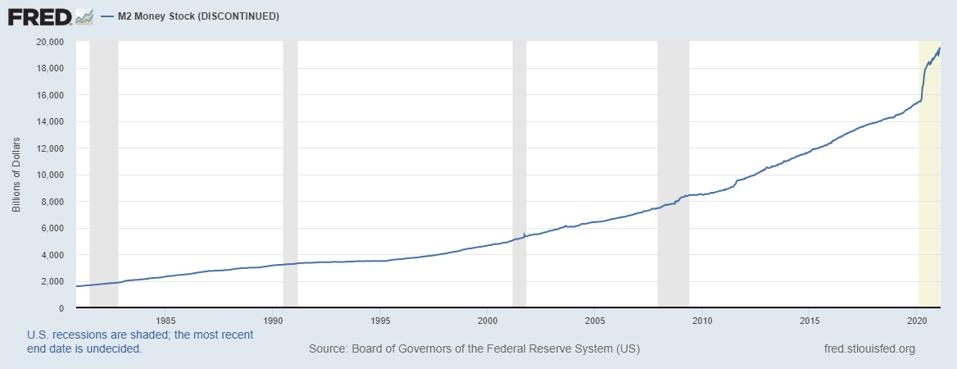

Westerners, in particular, find it difficult to understand how a 12-year-old digital currency dubbed “magic internet money” could be safer to hold than the US dollar, which has long been recognized as the world’s only reserve currency. The answer is actually quite simple: the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, exploits the trust placed in it by inflating the money supply to achieve its macroeconomic goals. As Federal Reserve chief Neel Kashkari said in a now-infamous interview with CBS: "There is no end to our ability to [flood the system with money] ... There is an infinite amount of cash at the Federal Reserve."

America’s M2 money supply, which measures the total supply of USD in circulation as cash, in ... [+]

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUISThe rights or wrongs of this approach can be debated elsewhere. What is not open to debate is the simple fact that printing money does not, by itself, create wealth. And if total wealth remains constant, then a higher money supply translates to a lower proportional value for each individual unit of currency–in this case, each dollar. That’s a roundabout way of describing inflation.

The same pizza can feed two people or it can feed ten people. The act of feeding more people does not magically create more food. To the contrary, everyone gets less.

Small wonder that the citizens of Latin America–a relatively poor region with a history of hyperinflation–embrace this concept so readily. They have bitter personal experience: in Venezuela, local currency the bolivar has been devalued so egregiously that banknotes are now worth more as novelty items than as cash. That will not happen to the dollar. But a steady decline in its purchasing power through inflation is already happening. And it’s the citizens of developing nations with dollarized economies–like El Salvador–who are at the sharp end of Federal Reserve policy.

Why? Because, unlike the wealthiest Westerners, they are wholly excluded from the benefits of a higher money supply.

They cannot allocate their spare capital to assets that are nominally appreciating–property, precious metals, fine art and so on–because their spare capital is far too small to be efficiently invested(remember: $25 GDP per person per day). Worse, the majority of them can’t even earn interest to protect what meager savings they have: 70% of El Salvadorians are unbanked.

It is from this perspective that “magic internet money” with a permanently fixed supply becomes rather attractive.

There will only ever be 21m bitcoins in existence. That’s a maximum of 0.00269BTC (worth $108 at the time of writing) for every human alive today. If more global citizens embrace the currency, rising demand will unavoidably push up the value of each coin.

Ask yourself: what would you do if you lived in one of the world’s poorest countries, and you had a choice between building your life savings in dollars; building them in bitcoin; or splitting your money between the two? Would you place your trust with a foreign government who you hope will act in your best interests; would you place it with a global community of geeks who claim to be democratizing finance with new technology; or, would you hedge your bets? For many people under 30, the first option is the least attractive.

But what about those concerns I voiced earlier? Let’s address each individually:

- Store of value: it is true that bitcoin is an unpredictable store of value. No-one knows what the price will be tomorrow, and crashes of 80% have happened multiple times in its history. Look beyond short-term price movements, however, and its long-term performance is remarkably attractive. Over the past decade, bitcoin’s average annual return is 891%. That will not last forever: with greater adoption, the volatility will smooth out. But having a fixed supply ensures that bitcoin will always be deflationary. It will always appreciate against inflationary currencies.

- Unit of account: to dismiss bitcoin today because people cannot price goods reliably in BTC is the logical equivalent of dismissing automobiles in the early 1900s because they were ill-suited to cobbled roads. The naysayers are correct: bitcoin does not function as a unit of account today. Nor will it for a long time. That is not a valid reason for dismissing its long-term prospects.

- Medium of exchange: the willingness and ability of El Salvadorians to transact in bitcoin will be determined by one group of people: El Salvadorians. It is not for me to advise them, nor should they look to foreign institutions or governments for impartial guidance. The only point I would stress is that bitcoin’s transaction fees do not pose an obstacle to adoption. Like any technology, bitcoin evolves. The Lightning network is a secondary layer being built on top of the primary blockchain which allows millions of dollars of value to be transmitted for pennies. Strike, the digital wallet favored by El Salvador’s government, is a pioneer of Lightning. El Salvadorians will not be paying $10 in fees to buy a $1 newspaper–in truth, it’ll probably cost about $0.01.

El Salvador’s decision to recognize bitcoin as legal tender should not, by itself, persuade anyone about the merit of cryptocurrencies.

What it should do is present a case study to the rest of the world about how developing nations can liberate themselves from US financial hegemony. It is deplorable that the richest people on the planet have become wealthier during the covid-19 crisis, due almost entirely to the self-serving monetary policies of central banks in the West. That those same policies are making the world’s poorest citizens even poorer–through debasement of USD cash holdings and inflation of global property markets–adds insult to injury.

El Salvadorians have the strongest possible incentive to make a success of their bitcoin experiment.

If they achieve this, more Latin American, African and Asian countries will follow suit. Many seem determined to do so regardless. And with each new country that takes the plunge, deflation will reward the earlier adopters with disproportionately high capital growth. Those citizens who choose to save a percentage of their money in bitcoin will–perhaps for the first time in their lives–be holding an asset class that meaningfully impacts their quality of life.

The best part? The very last countries to sign up to the bitcoin standard will be those who have the most to lose: Western nations, whose monetary systems directly benefit from the inability of developing nations to create and preserve wealth.

Surely that’s music to the ears of everyone who cares about fighting global inequality.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.