Though the U.S. stock market may win its current battle with the bond market, it could lose the war.

Based on a simple regression model built on the historical relationship between stocks, bonds, interest rates, and inflation, investors can expect stocks to perform about 3.3 percentage points better than bonds annually over the coming decade. But that doesn’t mean equities will produce a return that is anything close to their historical average.

Currently, for example, the bond market recently signaled that the 10-year Treasury will produce an inflation-adjusted loss of 0.7 percentage points annualized over the next decade. (That’s the difference between the 10-year yield and the 10-year breakeven inflation rate.) Assuming the econometric model is right, that means U.S. stocks will beat inflation by 2.6 annualized percentage points between now and 2031 — only slightly more than a third of its long-term average.

What this in effect means: While the stock market may be overvalued, the bond market is even more so. How you respond is therefore a function of whether you base your asset allocation on relative or absolute returns.

One who has made a big splash recently focusing on stocks in relative terms is Robert Shiller, the Yale University finance professor and Nobel laureate. He argues that stocks’ otherwise expensive valuations are cheap when viewed in relation to today’s rock-bottom interest rates.

Shiller’s arguments raise more than just a few eyebrows, since for years he was assumed to be solidly in the bearish camp. His Cyclically-Adjusted Price Earnings ratio (CAPE), otherwise known as the Shiller P/E, has been well above-average for several years now. It currently is higher than 98% of all monthly readings since 1881, exceeded only by the even-loftier levels registered at the top of the internet bubble in the late 1990s.

Both perspectives can be correct. Stocks may be cheap relative to bonds, even if they are expensive in their own right.

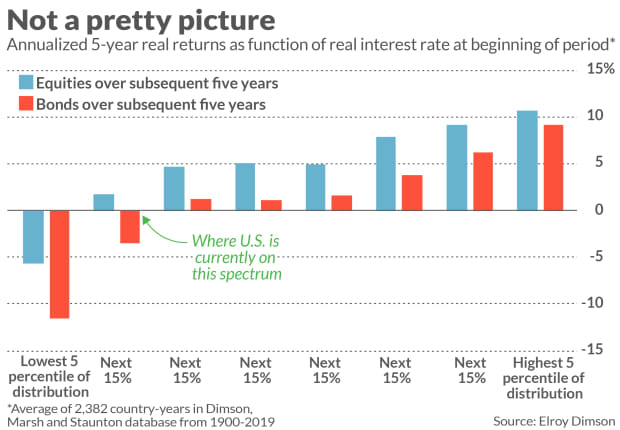

This distinction between relative and absolute is illustrated by the chart below. The data points in the chart were calculated by Elroy Dimson, a professor at Cambridge University’s Judge Business School and chairman of its Centre for Endowment Management. Dimson also is co-author of Credit Suisse’s Global Investment Returns Yearbook, which is based on the complete return histories for the stock and bond markets in 23 different countries dating back to 1900.

Dimson took all the countries and years in his database, a total of 2,382 separate observations, and segregated them into eight groups: The first and eighth contained the 5% of country-years with the lowest and highest real rates, respectively. Groups 2 through 7 contained successive 15% of the observations. For each group, he calculated bonds’ and stocks’ average real returns over the subsequent five years.

Several stark patterns are evident from the chart. Stocks outperformed bonds in all eight groups. But notice that returns for both assets were consistently higher, as real interest rates at the beginning of the five-year periods were themselves higher.

Notice also from the chart where the U.S. currently stands on this spectrum of real interest rates. While the U.S. is not in the lowest category that is associated with negative real equity returns over the subsequent five years, its stock market is disturbingly close.

Where to turn?

It’s important that we consider stocks from both relative and absolute perspectives. But many of us focus on equity valuations in relative terms only, which is dangerous.

If you needed a reminder why, recall the housing debacle in 2008. Each house was valued for mortgage purposes relative to other houses in its neighborhood. But those relative valuations proved to be of little solace when the whole market collapsed. It’s not out of the question that a similar scenario could play out in the stock and bond markets.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy figuring out where to turn in an investment environment in which everything is expensive. It’s probably easier to know what not to do.

One option that seems particularly dangerous is going further and further out on the risk spectrum. Yet it appears that many investors are aggressively betting on highly speculative investments. A few of these securities will likely reward investors, but history shows that, on average, they will underperform the broad stock market on a risk-adjusted basis.

My hunch is that we need to face squarely that we’re entering an extended era of low returns for all financial assets. Painful as that realization is, we need to adjust our financial and retirement plans accordingly. The sooner we plan for modest returns, the more likely the necessary adjustment will be less painful.

This article originally appeared on MarketWatch.