(Bloomberg) Dan McCabe is on a quest to transform your finances. The chief executive officer of Bedminster, N.J.-based Precidian Investments has a new way to invest that could make thousands of mutual funds obsolete, and he’s persuaded the likes of BlackRock Inc. to license the idea.

His big pitch? An exchange-traded fund that hides its holdings. Active managers have largely steered clear of the rapidly expanding $4 trillion U.S. market for ETFs, fearing that the daily disclosure these funds require would compromise their secret sauce. But McCabe’s patented structure allows ETFs to report once a quarter, like a mutual fund, protecting that intellectual property. As a result, stockpickers’ most popular strategies could be coming soon to an exchange near you.

The growing popularity of passively run funds—like most ETFs—has drained active managers’ assets. Index-huggers now manage about 40% of assets in the U.S., up from less than 10% two decades ago, according to Morningstar Inc.

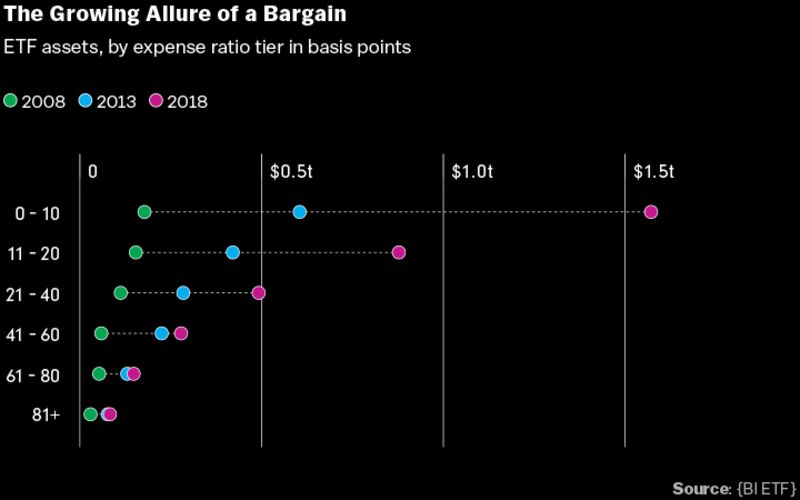

Cost is a major factor behind this shift. Tracking an index is cheaper than hiring a star manager, but that’s not the only reason ETFs are pushing management fees toward zero. ETFs are also inherently cheaper than mutual funds because they don’t need the same administrative support: They don’t maintain a record of their owners, they typically don’t pay incentives to distributors, and they shield investors from capital gains taxes by using securities to pay off redeeming fund holders.

By eliminating these costs, active funds could charge a lower fee, allowing the merits of their investing strategies to shine through—in theory, at least.

In his 35-year career on Wall Street, McCabe has seen changes in regulation and technology disrupt the business model of trading stocks and options. After working in sales, options trading, and index arbitrage at various brokerages, he rose to lead Bear Hunter Structured Products LLC, a unit of a so-called specialist that helped make markets on the New York Stock Exchange and American Stock Exchange. But new Securities and Exchange Commission rules in 2007 ushered in an electronic age, weakening the grip that specialists and exchanges had on markets. Today, computerized high-speed traders such as Virtu Financial Inc. and Citadel Securities rule the markets, including arbitraging ETFs.

So more than 10 years ago, McCabe and his partners—all from sales and trading backgrounds—turned to reinventing active money management, another business that was being disrupted.

Now 55, McCabe has spent the last decade educating regulators, asset managers, and brokers about how to trade a fund that doesn’t disclose its holdings every day. To price conventional ETFs, market makers use real-time information about the value of a fund’s holdings. When a fund’s price falls below the aggregate value of its components, these electronic traders step in to buy shares in the fund and redeem them for the underlying securities, profiting from the difference. This arbitrage keeps the price of the ETF in line with its value—but it requires portfolio transparency.

Under McCabe’s model, market makers will use an indicative value of the holdings published by the fund every second to judge whether its price is too high or low, rather than scrutinizing its portfolio. And when they buy discounted ETF shares to redeem for higher-value holdings, they won’t deal directly with the fund or end up with those stocks. Instead, an agency broker will confidentially receive the securities and sell them for cash that it returns to the market maker. McCabe’s structure finally secured regulatory approval in May.

“By the nature of the product, there are going to be wider spreads on account of the additional uncertainty—especially in the early days,” says Craig Messinger, CEO of Virtu Americas, a broker-dealer affiliate of Virtu Financial. “But we have a good idea of how to price this. You’re going to have a good universe of market makers.”

Investors may prove tougher to attract. The S&P 500 index of U.S. stocks gained more than 35% in the five years through 2018, and it’s available via an ETF at just 30¢ for every $1,000 invested. By contrast, fewer than 1 in 5 funds that actively picked U.S. large-capitalization stocks beat that benchmark over the same period, data from S&P Dow Jones Indices show. The lower embedded costs of ETFs can help stockpickers be competitive on expenses, but they won’t transform a dud strategy into a success.

Put simply, can an ETF structure save active managers?

“It’s packaging something that people haven’t wanted for years,” says Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research at Morningstar. “The challenges that [active managers] face in picking good securities that do at some point in time prove to be underpriced still apply here, and there’s still a fee to be considered.”

These new ETFs won’t necessarily be particularly cheap. Active managers want to charge a premium over index-tracking funds to compensate their stockpicking efforts and may wish to discreetly finance distribution efforts. As Messinger says, trading costs for these funds could also be higher. The regulator wants offering documents to make this clear.

And then there are the alternatives. T. Rowe Price, Fidelity Investments, the New York Stock Exchange, and Blue Tractor Group have all proposed different ways to create ETFs based on actively managed strategies with less frequent disclosure. While none has won regulatory approval yet, they could one day vie with McCabe’s structure for investor attention.

For now, the ActiveShares idea is gaining traction. American Century Investments is moving to list growth and value funds using McCabe’s design, Gabelli Funds has sought permission to start 10 strategies, and other licensees include Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Capital Group, and Legg Mason, which owns 20% of McCabe’s company. Licensing the structure is free; asset managers will pay a portion of their revenue only as these funds attract assets.

The struggle to get to this point reminds McCabe of the decade of tribulations endured by the eponymous hero of Homer’s The Odyssey, a favorite book from high school.

“If I had known at the time it was going to take that long, and the effort—it was going to be that hard or that expensive—I probably wouldn’t have started it,” he says. “But when I’m an old, gray man someday, I’ll look back on this as a tremendous accomplishment to be able to move a market as massive as this—hopefully in a very good direction.”