When your core strategies can’t cushion the crash or outperform on the upside, even a little operational disruption is a dangerous thing.

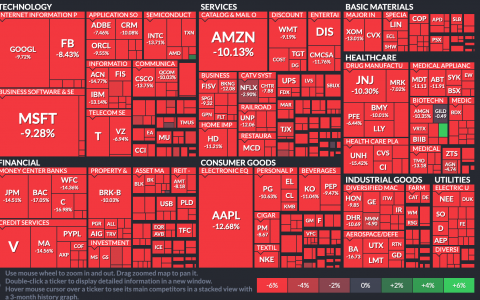

Last quarter blew out almost everybody’s models, but some of the most prestigious managers around did worse for investors than a vanilla index fund.

Dimensional Funds, for example, is now running 3-5% behind the benchmark YTD throughout its core equity portfolios and most are underperforming across the one- and three-year periods as well.

That’s nothing worth bragging about. And when fee drag on the vanilla funds has effectively dropped to zero, it’s hard to support sticking with solutions that cost more and objectively provide less.

Institutional money has started pulling money out of DFA and similar premium portfolios. Let’s see how deep the retreat gets this time.

The core becomes a drag

DFA has truly transformed the investment landscape, don’t get me wrong.

Advisors who qualify to work with the company rely on the relationship as a competitive differentiator. It’s a good thing.

In theory, DFA funds are more efficient and offer investors a real chance to beat the benchmark.

Performance in the good times made clients happy and reasonable fees provided compensation when returns got compressed.

That’s how the company grew from elite cult phenomenon to market heavyweight, ultimately attracting a little over $600 billion so far.

Once-obscure DFA is now one of the 40 biggest fund complexes on the planet, outranking brands like Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo and HSBC on a pure AUM basis.

But the way DFA rebalances its indices toward small value just hasn’t paid off lately. Value has been a drag and continues to be a drag.

As a result, most of the company’s now-sprawling universe of funds was behind the benchmark as of April 30, including flagships like DFLVX and DFUVX.

Investors who bought into either of those funds three years ago have lost money while the S&P 500 surged 9% a year. Even the value index has eked out a slight gain over that period.

And while fees aren’t enormous, paying a net 0.14% still grates when boring old SPY charges less and provides so much more.

Investors pulled about $10 billion out of DFA last quarter in pursuit of a better proposition elsewhere. Since the long-term flows remain positive, I’m thinking this is a fee-for-performance issue.

DFA also saw $4 billion in negative flows at the end of last year, when the market was chasing records and enhanced return strategies should have had clients feeling even better than their peers.

Last year was all about trillion-dollar fund complexes cutting fees to starve rivals. You have to justify every basis point. Otherwise, boring old SPY is good enough.

“Avoid losing money”

Furthermore, value stocks just haven’t lived up to their historically defensive reputation lately. When the market shuddered, DFA clients felt the shock too.

Do the math: a fund family starts 2020 with $609 billion under management and reports $454 billion on March 31. Factor out moderate redemptions and about 24% of the capital invested with DFA managers evaporated last quarter.

That’s a huge and nightmarish drawdown. Those who hoped the models would cushion their portfolios from the worst of the volatility have been disappointed.

Of course DFA is not alone here. I’m not singling them out for doing anything wrong. They stuck to their models and most models caved in.

But some didn’t. More nimble and responsive portfolios negotiated the drawdown in various ways, sitting out the worst selling in bonds or cash.

Even the S&P 500 beat the DFA universe by 3 percentage points over that period. Pure index fund investors aren’t happy either, but there was no assumption of enhanced defense there.

And they were paying, what, 0.07% for full exposure to the upside as well as the downside?

Over the trailing three-year period, DFA has outperformed in various fixed-income segments like muni bonds as well as real estate and commodities.

Truly enhanced factor models focused on earnings quality (“relative profitability” and tax-sensitive portfolios have also held up well.

Funds like these are the future of differentiated money management. They’re how the scientists justify their fees and their continued presence in the market.

You can chase higher returns. You can cushion volatility. People see the added value either way and will pay a fair price for it.

And when they can’t see the value, they’ll go elsewhere. It happens.

Over the long random walk, DFA’s methodology should come back stronger than ever. For now, in an increasingly short-term world, it’s a tough sell.

Compression and attention

The response so far has been to compete on pricing. Back in February, before the market downswing really accelerated, DFA shaved a few basis points off 77 funds.

This is nothing new. As management noted at the time, fee compression at DFA has been going on since 2015. It’s simply part of the industry competitive landscape now.

Admittedly, the bigger you get, the easier it gets to simply coast on scale. You can charge less and still make money.

But in the face of bigger players like Vanguard, Fidelity and Blackrock, rival funds simply can’t compete on cost alone. The giants can and will go all the way to zero.

And bigger funds can get stuck in their own footprints. It gets harder to make truly contrarian trades.

Where you once fought to beat the market, you now end up converging with “the market” purely because you represent a much bigger piece of it.

You become a de facto index fund. That’s not a bad thing. Reading between the lines of DFA’s interest in target-date portfolios and more recent bundled “wealth models,” that’s where the company is headed.

Mass products for the mass affluent, priced to squeeze every possible basis point out of a fragile retirement account. Maybe they’re robo killers. It remains to be seen.

But conventional high-net-worth investors who want personal attention and institutions that simply demand the best spot on the efficient frontier their fees will buy, it feels a little strange.

When the models crumpled, DFA didn’t change course. In the long haul, that’s probably a good call, but in the short term it can look like the autopilot got stuck.

Maybe they were distracted trying to work from home with kids in the background like the rest of us. Their office was shut down because they weren’t an essential business, I get it.

The challenge is that the advisors they work with don’t have that excuse. We’re all facing enormous disruptions every day.

Some rise to the occasion and others let the disruptions wear them down. Institutions have their stakeholders to answer to. You have your clients.

Robo Nation doesn’t really mind. They’re used to being another faceless account number on the random walk.

I’m looking forward to seeing what the geniuses who built DFA come up with next. Maybe there’s long-term value in thinking small.