(Bloomberg) Thanks to advances in computer-generated imagery, James Dean is about to star in a new film—more than 60 years after his death.

To make it happen, the filmmakers needed his heirs’ permission because he died as a California resident. California law grants heirs transferable post-mortem right of publicity, the ability to control commercial use of someone’s name, image or likeness, for 70 years.

Placing Marilyn Monroe in a new movie would have been far easier because her estate, for tax reasons, decided in 1962 that she died in New York, which has no such heritable right.

Advancements in CGI technology will push the boundaries of a patchwork of state right-of-publicity laws if reviving dead stars proves lucrative, attorneys say. It also gives actors, celebrities and their lawyers something to think about when writing their wills—and deciding where to call home as they grow older.

“New technology always precipitates litigation sooner or later. I have no doubt this will end up in litigation one way or another,” Amy R. Lucas, an intellectual property attorney for O’Melveny & Myers LLP who works in the movie industry, said. “Celebrities need to think very long and very hard about how they want their right of publicity to be used after they die.”

‘Where Else Can It Go?’

Dean’s casting in a new Vietnam-era movie called “Finding Jack”—after Elvis Presley’s estate said no—raises the specter of reviving dead celebrities for new productions on a much broader scale than finishing a movie after a key actor’s death.

The most typical use of CGI actors traces back to “The Crow,” which was finished after star Brandon Lee was killed in a 1993 on-set gun accident near the end of filming. CGI revived long-dead “Star Wars: A New Hope” actor Peter Cushing’s imperial-military-officer character from the 1977 original movie for 2016’s “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.”

The soon-to-be-released “Star Wars: Rise of Skywalker,” will use unused footage from prior movies rather than CGI to depict Princess Leia, played by Carrie Fisher until her 2016 death, director J.J. Abrams has said. So it’s Dean’s revival that presents a test case for CGI as a viable casting choice.

“Studios are asking themselves, ‘let’s see how this goes, and if people like it where else can it go from here?’ The implications are numerous,” Lucas said.

Living actors in theory could license themselves to several movies, and owners of post-mortem rights could license them if they’re not already public domain, harnessing vast reservoirs of nostalgia, Lucas said.

“Can you imagine seeing Frank Sinatra again? Among an older generation, there is enormous market potential if it’s done right,” Lucas said.

Multiple attorneys doubted CGI would spawn a free-for-all, particularly without heirs’ permission. The movie industry is composed of “the most conservative folks” who would avoid legal gray areas with even potential to set back production in the event of a lawsuit, intellectual property attorney Raymond J. Dowd of Dunnington Bartholow & Miller LLP said.

Studios also tend to try to avoid offending talent or audience sensibilities.

“I think it’s unlikely a movie studio is going to do it in a blatant way, because of relationships with talent and the uproar it would create,” intellectual property attorney Cynthia S. Arato of Shapiro Arato Bach LLP said.

Uncertain Rights

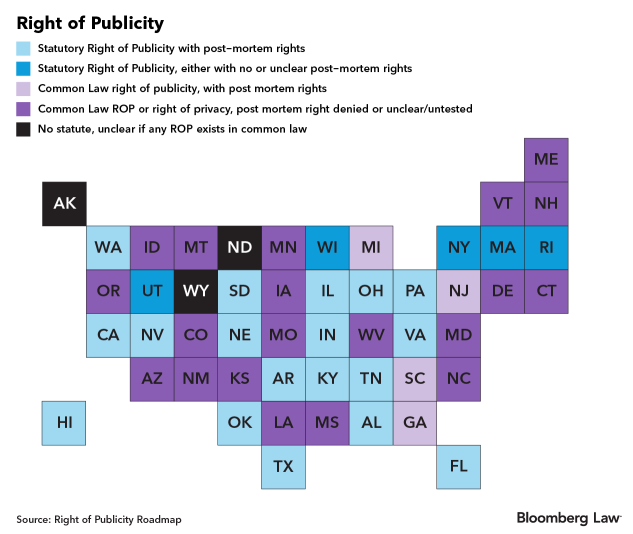

Right of publicity varies widely across states, as there’s no federal law. Nearly half protect it by statute. Most of the rest have common law precedent holding that other laws protect similar rights. Federal trademark law’s false endorsement provisions provide a limited backstop, but require a showing of consumer confusion.

After death, complications multiply. At least 20 states protect posthumous right of publicity as a heritable property right, mostly by statute. Some states have varied common law protections of post-mortem rights, courts in other states have rejected them while in still others the question remains untested.

“I think there’s no question that if you’re looking forward to being a dead celebrity, you’re better off in California than you are in New York,” Dowd said.

Right of publicity protections range from zero to 100 years after death, and some states have no time limits if continually used. Some require a persona to have value at time of death; others protect everyone. Louisiana only protects deceased soldiers.

Minnesota’s legislature introduced the PRINCE Act weeks after the music superstar’s 2016 death to solidify protection of post-mortem rights for 50 years, but it didn’t pass. That effort echoed what happened in Tennessee, where post-mortem publicity rights law stemmed directly from Presley’s 1977 death. A Minnesota federal court in 2017 held the state has heritable common law publicity rights in a pending case.

New York, a celebrity hotbed, has frequently considered extending post-mortem rights. But competing interests, such as the actors unions and movie studios, have stymied legislative efforts, Arato said.

“The legislature keeps coming with a bill. Everyone seems to think it’s going to pass, and it doesn’t,” she said.

Locking It Down

Heirs of stars who died in states without protection have sought other avenues to assert rights.

Monroe’s estate sued four photographers in 2005 in Indiana for exploiting their photos of the actress under that state’s law, which grants 100 years of posthumous rights to anyone, no matter where they died. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in one case shifted to New York that Indiana’s 1994 law couldn’t confer rights to the estate, as it didn’t exist when she died.

New York’s lack of protection also affected a feud in which Jimi Hendrix’s father tried to claim exclusive rights against Hendrix’s brother after the guitarist’s 1970 death in New York—citing Washington law. In response to a Ninth Circuit finding in that case that New York law applied and no one owned Hendrix’s image, Washington’s legislature extended its post-mortem publicity rights to those who’d never lived in Washington. But the Ninth Circuit in 2011 struck that down as unconstitutional.

“It’s insane to have clear amount of value in California, but if you happen to live in New York, you’re out of luck. Especially if exploitation by and large is taking place in California or nationally,” Lucas said.

Planning forpotential virtual immortality presents a new factor when preparing for physical mortality, along with divvying inheritance shares and tax planning. Some celebrities have better considered who will guide their legacy once they exit stage right than others.

One of the most far-reaching planners was actor-comedian Robin Williams, who committed suicide in 2014. His will passed his California-based rights to a foundation and prohibited any commercial use of his image until 2039. Prince, meanwhile, died in 2016 without a will and litigation continues over inheritance of his estate.

“If I were a celebrity, I would definitely want to be sure my will and trust were locked down,” Lucas said. “God forbid it goes to a random cousin in Indiana who lets it be used in reality shows, or some really awful movie, or X-rated movies.”