The debate over the traditional 60/40 portfolio seems endless, but for pensions at least, it’s over -- and bonds won.

The retirement funds of the top 100 U.S. public companies, with combined assets of about $1.8 trillion, have ratcheted up their fixed-income allocations to a record level. At the end of their last fiscal year, they held 50.2% of assets in debt, while slashing money parked in equities to an all-time low of 31.9%, according to a recent report from pension advisory firm Milliman Inc.

The shift, part of a longer-term transition spurred by federal legislation that made fixed-income more appealing, is gaining momentum even though asset class returns have gone in opposite directions with stocks surging to record highs while a four-decade rally in U.S. bonds is in jeopardy. Analysts see the emphasis on debt by the funds accelerating, and maybe most significant, potentially helping to blunt any move higher in yields.

“The big improvement in funding ratios implies a high incentive” for “U.S. private defined benefit pension plans to lock in the recent gains in their funding position by accelerating their de-risking going forward,” a team of JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists including Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou wrote in a recent note. That means “accelerating their buying of long-dated bonds and selling of equities.”

Hard shift toward fixed income securities persists

Corporate pension funds' share in debt rises to over 50%

Source: Milliman Inc.

Note: Pension funds of top 100 public companies tracked by Milliman

Pension funds tend to follow a strategy of matching liabilities -- which are usually long term -- with similar maturity assets, usually debt. Even though rising yields can hurt returns in the short-run, they’re a plus since they can help reduce the present value costs of obligations.

Paltry yields that seemingly have nowhere to go but up have been an almost universal worry that has prompted investors to question the wisdom of sticking with the long-favored portfolio diversification recommendation of 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

Ten-year Treasury yields have risen over a percentage point since August, nearly reaching 1.8%, as an improved vaccine rollout sparks business reopenings amid trillions in fiscal stimulus. The jump in yields resulted in the worst quarter for Treasuries since 1980, and has prompted Wall Street to predict even higher yields before year-end. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 index climbed 5.8% in the three months ended in March, the fourth consecutive quarterly increase.

Until last quarter, it’s mostly been the best of both worlds for pension funds, with equities outperforming long-duration debt even as yields plunged over the past few years. That generated gains that exceeded increases in pension liabilities.

Matt Levine's Money Stuff is what's missing from your inbox.We know you're busy. Let Bloomberg Opinion's Matt Levine unpack all the Wall Street drama for you.

The funding status -- a measure of the degree to which pensions have enough assets to meet liabilities -- of the 100 companies tracked by Milliman was 88.4%. Since 2005, the funds have also increased their allocations to “other” investments including private equity, real estate, hedge funds and money market securities to 17.9% from 9.5%. The majority of the companies have a fiscal year end that coincides with the calendar year end.

“The main reason for the overall shift from equities into fixed income has had to do with the change in pension regulations,” said Zorast Wadia, a principal at Milliman. “And as these pensions’ funding status have improved they have continued to shed equity risk -- getting more and more into fixed income.”

Under the federal Pension Protection Act passed in 2006 companies had a set time to fully fund retirement plans and were required to use a specified market-based rate of return -- tied to corporate bond yields -- to compute liabilities rather than their own forecasts. This change made buying debt in an asset-liability matching framework more appealing than equities.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the most recent Covid-19 pandemic relief bill, provides two forms of general funding relief for single-employer pension plans. It’s not clear yet if that may affect asset allocation decisions.

JPMorgan predicts that public pension funds run by states and local governments are also on course to shift more into fixed income. These public defined benefit plans, with about $4.5 trillion in assets, have a funding status that trails their private-sector peers, at about 60%.

“So public pension funds have less incentive to de-risk in general,” Panigirtzoglou wrote. “But they do face a problem. Their equity allocation is already very high and their bond allocation stands at a record low of 20%. So, from an asset/liability mismatch point of view they are under some pressure to buy bonds.”

On the surface, any preference of fixed income makes little sense. Since 2005, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index increased about 5% annually, about half the S&P 500’s return. But when adjusted for volatility, equity performance was 23% worse than bonds.

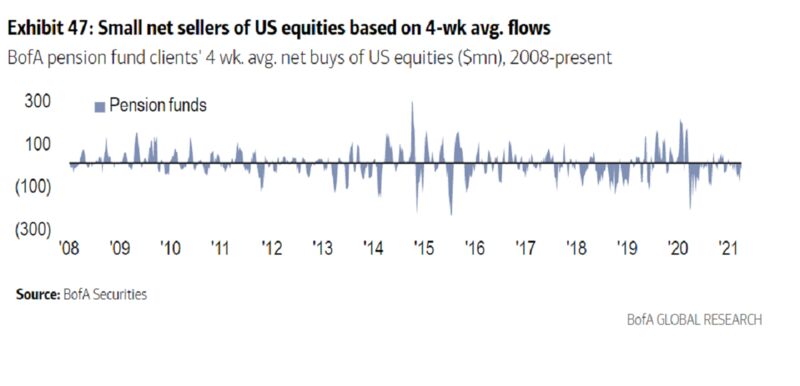

While optimism about the bull market in stocks seems endless, aversion among pension funds persists. This month, Bank of America Corp.’s pension fund clients have been net sellers of stocks, extending a year-long trend of outflows.

What corporate pension plans “are looking for is to be well funded, not necessarily to get strong returns,” said Adam Levine, investment director of Aberdeen Standard Investment’s client solutions group. “It is possible that as rates rise, corporate pensions move enough to the fixed income that to some degree it counters the rise in rates. You can certainly make that case if the moves are big enough and the industry is big enough.”

This article originally appeared on Bloomberg.